|

| Pete's Tavern Token, front and back |

Now saddled with a Pete’s Tavern token, I set about researching tokens in an effort to learn when it was made, trying to see whether or not the token was connected to the Pete's Tavern I had read about in the newspaper articles from 1949.

The available material about merchant tokens was entirely unhelpful, as it was all too generalized. From what I read, my token could have been produced anytime between the 1880s and the 1940s.

Next, I tried skimming the Waterbury City Directories for Pete’s Tavern. Here’s where things started to get interesting.

During the 1880s, Waterbury had several “Sample Rooms” where you could purchase ales, wines, liquors, lager beers, and cigars. Other businesses did not call themselves sample rooms, but offered the same products. Nearly all of the businesses were known simply by the name of the proprietor, which was always the owner’s full name (Frank M. Ehle, Henry Menold, and Napoleon Gette, for example) or last name if there was more than one owner (Borchardt & Bartz, for example).

|

| Peacock Sample and Pool Rooms advertisement Waterbury City Directory, 1885, p. 434 |

|

| Clark H. Nichols Sample Room advertisement Waterbury City Directory, 1885, p. 432 |

|

| John Sandom Liquor Dealer advertisement Waterbury City Directory, 1885, p. 433 |

I deduced that Pete’s Tavern could not possibly exist during the late 1800s. No one would have used the nickname “Pete” for his business, and nothing was referred to as a tavern.

I jumped ahead to the 1919 City Directory, the last publication year before Prohibition started. Again, no taverns – saloon was the official term used to describe that type of business – and liquor dealers still preferred formal names, not nicknames (Drescher & Keck, T. H. Hayes, etc.).

|

| Drescher & Keck advertisement Waterbury City Directory, 1919, p. 68 |

|

| The Hodson Brothers' Company advertisement Waterbury City Directory, 1919, p. 68 |

I jumped ahead once more, to 1934, the year after Prohibition ended. All of a sudden, tavern was an official category in the City Directory. The following year, 1935, there was just over half a page of taverns listed. This would grow to a full page of taverns in the 1937 City Directory.

In 1935, there was a Patsy’s Tavern at 790 North Main Street, confirming that I was in the right time period for a Waterbury business to be known as Pete’s Tavern.

Two of the new taverns of 1934 were possible candidates for my Pete’s Tavern token: Peter P. Palapis at 319 Bank Street and Peter A. Valunas at 776 Bank Street. Neither of these is the Pete’s Tavern I read about in the 1949 newspaper articles. That tavern, as it turns out, was formally known as Peter’s Restaurant.

I found one more possible candidate for the Pete’s Tavern token: Peter J. Griffin operated a tavern at 51 Fuller Street during the 1940s.

After browsing the City Directories, I was left with several unanswered questions: why were all of the bars called taverns after Prohibition ended? How much beer could you buy for ten cents (the value of the token) in any given year? Which Peter was the Pete’s Tavern token owner? My search for answers unveiled an interesting history of taverns in Waterbury.

Repeal of Prohibition

I first learned about Prohibition during a high school history class, part of a series of lessons about the 1920s. The way I remember it from school, Prohibition led to speakeasies, bootlegging, and a surge in organized crime. It ended during the Great Depression because, well, everyone needed a drink. There are, undoubtedly, some flaws in my memory of history class. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby figures into my memories of these lessons, but now I visualize Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby, even though he didn’t play that role until decades after I finished high school. Memory is funny that way.

The end of Prohibition started in February 1933, when the U.S. Congress proposed a new Constitutional Amendment to repeal the Amendment banning alcohol. The new Amendment was ratified less than a year later, on December 5, 1933. This part is what I remember from high school, nice and simple, with a couple of easy dates to remember, conveying a general understanding of an important process.

|

| Presidential Campaign Button of 1932 showing Franklin D. Roosevelt and John Nance Garner's support for the repeal of Prohibition. Image from The Mob Museum's Prohibition website. |

What I didn’t learn in high school (or maybe I forgot) is that Congress legalized beer and wine with a low-alcohol content (3.2% by weight) before Prohibition was officially repealed. The Cullen-Harrison Act of March 21, 1933 opened the doors for legal alcohol even if the repeal of Prohibition didn’t succeed. Four weeks later, despite strong opposition from Connecticut’s Republican politicians, our state legislature approved the legalization of 3.2% beer and alcohol and established a State Liquor Control Commission to oversee its regulation (“State Liquor Control Plan Passes House,” Hartford Courant, 19 April 1933, p. 1).

State Liquor Law of 1933

The State Liquor Control Commission put in place measures intended to control the “evils of the old-time saloon,” as described by an editorial in the Waterbury Republican ("Sane Liquor Control Needed," Waterbury Republican, 6 April 1933, p. 8).

Specific classifications allowed to sell alcohol were manufacturer, wholesaler, package store, hotel, restaurant, club, tavern, railroad, boat, and druggist. Each classification was required to pay for an annual permit; manufacturers paid the most, $1,000 per year, while taverns, railroads, boats, and druggist paid the least, $50 per year. Only package stores and drug stores were allowed to sell “spiritous liquors” and only drug stores could sell prescription or medicinal compounds involving alcohol. ("Fees for Permits," Hartford Courant, 1 April 1933 p. 13)

So here’s the answer to one of my questions. During the 1930s, Connecticut's bars were all called taverns, because that was the official state designation for that type of business. Taverns, unlike the saloons that preceded them, were limited to selling beer; the sale of liquor was not permitted.

Hotels were allowed to sell only beer and wine in their dining rooms with meals, and they were specifically barred from allowing “the public consumption of spirits” in any public room of the hotel. Similarly, restaurants and clubs were allowed to sell only beer and wine, while taverns were allowed to sell only beer, no other form of alcoholic beverage. Taverns were further restricted in their physical setup – they were required to maintain a full and unobstructed view of their interior from the main entrance or from the street; curtains and other forms of screens were prohibited. Additionally, taverns could not be located within 200 feet of a church or school. (“100 Sections in New Liquor Law,” Hartford Courant, 21 April 1933, p. 22)

Liquor could be purchased from pharmacies with a prescription (patent medicines typically featured a high alcohol content). Package stores could not sell alcohol on Sundays, but hotels, restaurants, taverns, and clubs could. No business of any type could sell alcohol on an election day. The sale of alcohol to someone who was intoxicated was not permitted, with the seller being held legally responsible for any damage caused by the intoxicated buyer. The state tax on alcohol was set at four percent for retail sales and one percent for wholesale. (“100 Sections in New Liquor Law,” Hartford Courant, 21 April 1933, p. 22)

Happy Days Return

Connecticut set the date of May 10, 1933 for the official return of legal alcohol sales. Package stores were permitted to begin selling beer at 8 a.m., while hotels, restaurants, taverns, and clubs started selling at 9 a.m. A handful of Connecticut breweries were able to go into production before May 10, while the rest of the beer supply came from out of state. ("Cross to Proclaim Sale of Beer Legal In State Tomorrow," Waterbury Republican, 9 May 1933, p. 1)

Approximately forty permits were issued in Waterbury as of May 10, with an estimated 69,000 cases and 11,000 barrels of beer ready for Waterbury's drinkers. Some business owners drove to Hartford that morning to pick up their permits, rather than wait for them to arrive in the mail. ("Apathetic Public Greets Beer With Raised Brows; Salesmen Hustle In City," Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p. 1)

By May 11, an estimated 75 permits had been issued in Waterbury. In order to qualify for a permit, business owners had to pay $1,000 in cash for a surety bond, which limited the number of businesses who could apply. ("City Takes Its Beer In Mild Manner With Only Three Arrests," Waterbury American, 11 May 1933, p. 1)

The first four permits issued in Waterbury went to Hewitt Grocery Store, Mascolo Bottling Works, Diamond Bottling Co., and Clark Ramsay. A manufacturer's permit was issued to Largay Brewing Company. Hewitt was stocked up on the morning of May 10 with 500 cases of beer, of which 100 cases were reserved in advance. ("Only Four Places Ready to Offer City Beer Today" Waterbury Republican, 10 May 1933, p. 1)

Other Waterbury businesses which secured their permits in time for the May 10 rush included the First National Stores, Great A&P, and Howland Hughes ("City Sips Beer As Sale Opens; Permits Slow," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933, p. 10). Other applicants included the Elton Hotel, The Hodson Lunch, Drescher & Keck, and the Doughnut Shoppe, all of whom applied for restaurant liquor permits ("City Sips Beer As Sale Opens; Permits Slow," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933, p. 1).

Waterbury retailers sold an estimated total of 5,000 cases of bottled beer on May 10. Waterbury tavern permits were not issued until some time later; would-be taverns had to be inspected before being authorized. ("City Sips Beer As Sale Opens; Permits Slow," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933, p. 10)

Advertisers declared “Happy Days Are Here Again” as breweries rolled out their barrels of 3.2% beer. Hartford’s Aetna Brewing Co. went into 24/7 production and shipped bottles throughout Connecticut, including sending numerous crates to at least one Waterbury grocery store (“Hartford’s First Test of 3.2 Beer At Source,” Hartford Courant, 10 May 1933, p. 1 and “Well Boys, Here It Is At Last,” Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p. 4).

|

| Crates of beer from Aetna Brewing Company arriving at an unspecified Waterbury store Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p. 4 |

|

| Hartford Courant, 10 May 1933, p. 8 |

|

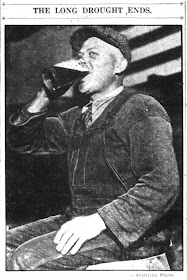

| Alex Sasso of Lounsbury Street getting his first taste of legal beer after 13 years of Prohibition. Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p. 4 |

Waterbury Brewers and Distributors

The famous Red Fox Ale, made by Waterbury's Largay Brewing Company, made its appearance on May 10, 1933. Largay had a glitch in selling beer on May 10 due to a shortage of barrels and bottling equipment, but they were up and running soon after ("Only Four Places Ready to Offer City Beer Today" Waterbury Republican, 10 May 1933, p. 1).

George Largay set up his brewery in the former Hellman Brewing Company building (closed in 1919 by Prohibition) in Waterbury's Brooklyn neighborhood. Red Fox Ale would later be supplied to the U.S. Army during World War II, expanding its popularity, but the small local brewery was ultimately unable to compete with national corporations and was sold in 1947.

|

Waterbury Democrat, 10 May 1933, p. 10 |

Waterbury’s Diamond Bottling Company was the official local distributor for Hartford’s Aetna Brewing Company. By May 11, they had sold several thousand cases of beer, mostly to dealers ("City Sips Beer As Sale Opens; Permits Slow," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933, p. 10).

Diamond was located on South Main Street in the Hopeville neighborhood for more than a century. They renamed themselves Diamond Ginger Ale, Inc. in the 1940s and moved to Watertown in the 1970s.

|

| Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p.9 |

Waterbury's Mascolo Bottling Works, located on East Main Street, was the Waterbury and Litchfield County distributor for New York's Utica Beers.

|

| Waterbury Democrat, 10 May 1933, p. 9 |

Wm. Laube Jr., a division of Laube Interstate, Inc., was the local distributor for Wehle Ale and Lager, a New Haven brewery. Laube Interstate was a trucking company located on South Main Street.

|

| Waterbury Democrat, 10 May 1933, p. 10 |

Retail Beer Sales

A number of Waterbury stores were ready for the return of beer sales on May 10, running advertisements in the newspapers that day. Package stores were able to sell beer between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m.; an unidentified Waterbury legislator was frustrated on May 10 when he tried to purchase beer after 7 p.m., leading a Waterbury American report to hope that the law might be revised to allow sales up to 9 p.m. ("Legislator Tries to Buy Beer After 7 P.M.," Waterbury American, 11 May 1933)

Clark Ramsey, at 103 Meadow Street, advertised 12-bottle cases of Budweiser, Pickwick Ale, Rheingold, and Fidelio. More than 1,000 cases of beer were sold at Clark Ramsey on May 10 ("City Sips Beer As Sale Opens; Permits Slow," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933, p. 10).

|

| Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p.10 |

|

Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p.18 |

The Hodson family owned a hotel, beauty shop, and lunch spot at Exchange Place from 10 through 20 Bank Street. They were ready for legal beer sales with beer on tap and a cheery advertisement that included a cartoon of a bartender carrying more than dozen frothy mugs of beer. On May 10, their lunch spot sold approximately 50 cases of beer and a small amount of draft beer with food ("City Sips Beer As Sale Opens; Permits Slow," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933, p. 1).

|

| Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p.14 |

What to Serve With Beer

The Waterbury Republican offered helpful tips for women adding beer to their dining tables (Martha Logan, "What to Serve With Beer," Waterbury Republican, 10 May 1933, p. 12). Sample menus included:

- Steak, french fries, buttered string beans, crackers and cheese, and a lettuce and tomato salad with French dressing;

- Corned beef, boiled potatoes, buttered cabbage, sweet mustard pickle, and baked apple;

- Smoked beef tongue, stuffed baked potatoes, buttered spinach chow-chow, and baked custard;

- Hungarian goulash, spaetzels, enrive salad with Roquefort cheese dressing, and apple pancakes;

- Beefsteak and kidney pie, boiled potatoes, boiled cabbage, an orange ice;

- Lamb or mutton chops, hashed brown potatoes, green peas, mushrooms, catsup, black current jelly, raspberries;

- Spare ribs, boiled potato and sauerkraut, mustard pickle, gingerbread;

- Baked ham, candied sweet potatoes and buttered spinach, raisin sauce, and pineapple pie;

- Pigs' knuckles, boiled potato and sauerkraut, chicory, French dressing, apple strudel;

- Weiner schnitzel, boiled rice, lettuce and tomato salad with French dressing, runne and apricot compote;

- Roast turkey, stuffed baked potatoes, buttered brussels sprouts, orange and celery salad, French dressing, and Dutch applecake;

- Cheese fondue, broiled tomatoes, lettuce, French dressing, and blackberry pie.

Related Products

Waterbury's Chase Companies was more than ready for the return of legal beer sales. The plumbing supply company had just launched its "Chase Specialties" line of Art Deco chrome and copper housewares (its first catalogue for that product line was published in 1933). The Waterbury Democrat newspaper published a sampling of the beer-friendly Chase products alongside articles about the return of legal beer sales.

|

| Waterbury Democrat, 10 May 1933, p. 10 |

The Chase art deco wares are highly collectible today. I was able to find recent photographs from online auctions of a few of the products in the 1933 newspaper article. The Heidelberg beer set, however, is one I can't find any reference to.

|

| Chase Specialties, "Pretzel Man," copper, 1930s Image from Worthopedia |

|

| Chase Specialties "Bacchus" goblets, copper, 1930s Image from Worthopedia |

|

| Chase Specialties Tavern Pitcher, copper, 1930s Image from Google Image Search/Pinterest |

The Price of Beer

The going price for a glass of beer at a tavern or restaurant in 1933 and even as late as 1949 appears to have been ten cents, the same price as a bottle of King's or Trommer's at Howland Hughes. Ten cents is also the trade value of the Pete's Tavern token. As I guessed, you would have been able to trade the token in for one beer.

Regulation of the price of beer was an open question when legalization began. The Waterbury Republican expected it to be "about" ten cents a glass, with bottle beer pricing starting at 15 cents a bottle for local beers and 20 cents a bottle for beer from out of state ("Cross to Proclaim Sale of Beer Legal In State Tomorrow," Waterbury Republican, 9 May 1933, p. 1-14). The Howland Hughes advertisement above, however, had much cheaper pricing listed.

By July 1933, the price of beer in Waterbury varied. For ten cents, you could get anywhere from five to ten ounces of beer, with a handful of restaurants offering a glass of beer for a nickel with specific sandwiches ("Waterbury Sees New Hope In 5 Cent Beer Demands," Waterbury American, 12 July 1933).

Each town's taverns appear to have been able to set the price of beer by town. Middletown's tavern owners formed an association which set the price of beer at ten cents for a 10-ounce glass at every tavern in Middletown. They also agreed that pretzels and cheese snacks could be provided at no cost to beer drinkers, but sandwiches would be sold, not free, to avoid competing with restaurants and lunchrooms. ("Beer Price Set At Dime By Taverns," Hartford Courant, 13 July 1933, p. 9)

Competition between restaurants and taverns was a recurring theme. An anonymous restaurant owner in Hartford wrote a letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant expressing fears that the state's 1400 taverns would be allowed to serve hot food, which could potentially put many restaurants out of business ("Taverns vs. Restaurants," Hartford Courant, 13 January 1934, p. 10).

While ten cents seems like nothing to us today, in 1933 there were people who found that to be excessively expensive. Waterbury's Everett Grilley, a laborer, complained about the high price of beer in a letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant. Grilley ended his letter by saying "...it's a fake and a sham and its heavy toll by taxes prevents the workman from his old fashioned 5-cent beer." ("Price of Beer," Hartford Courant, 18 May 1933, p. 12).

Prescription Liquor

Pharmacies were authorized to begin dispensing unlimited liquor prescriptions starting on May 15, 1933. Prior to this date, patients were limited to one pint (usually of whiskey) every ten days. The price of prescription pints was also decreased, from $2.50 and $3.00 to $1.25 and $1.50. ("No Limit on Prescriptions," Waterbury American, 10 May 1933, p. 4)

New Restrictions in 1934

|

| Carl Louis Mortison, "Father Connecticut Will Retain Control, Thank You" Waterbury Republican, 22 April 1934 |

The State Liquor Control Commission set new regulations for taverns starting in July 1934. Dimmed or colored lighting was banned, as was entertainment, music (vocal or instrumental), and dancing.

Lewis Lauria of Waterbury, former president of the State Liquor Dealers Association and secretary of the National Association of Beer, Wine and Liquor Dealers, spoke out against some of the new restrictions, but instead fully supported the restriction of women in taverns, which was not in the official restrictions. Lauria specifically criticized the original regulations on taverns because they did not bar women from taverns. Lauria also praised the many tavern owners who had foreseen "the danger of music and entertainment in taverns" and therefore never allowed such activities to occur in their taverns. In his view, the new regulations banning music and entertainment were unfairly punishing the "good" tavern owners due to "the promiscuous actions of disreputable tavern owners." ("Tavern Ruling Rouses Wrath of Waterbury Man," Hartford Courant, 7 July 1934, p. 3)

They types of entertainment that were considered problematic for taverns also involved pool and billiard tables, although tavern owners expressed concerns that slot machines were also being targeted. ("New Tavern Ruling Troubles Keepers," Waterbury American, 3 May 1934 and "Liquor Board Doesn't Want Pool Tables," Waterbury Republican, 3 May 1934).

John Delaney, president of the Waterbury branch of the Beer, Wine & Liquor Dealers' Association, acknowledged that some taverns had "gone too far" in allowing music and dancing "of a questionable nature," and that the use of low lighting "lowered the moral tone" of the taverns. Delaney stated that most taverns were reputable, with only a half dozen or so taverns in Waterbury having music or dancing "of an improper nature." ("Waterbury Tavern Owners Bitter At Latest Ruling," Waterbury Republican, 7 July 1934, p. 2)

The Waterbury Republican stated that only about 20 taverns had music and dancing, usually on Wednesday and Saturday nights. Two or three businesses on Bank Street had "gained quite a reputation" for their musical and dancing events and the "dim seclusion of booths due to the dim, colored lights." The paper also mentioned a number of taverns on the outskirts of town, including one at Hitchcock Lake in Wolcott, which had "built up their trade largely by the entertainment features" and would now have stick to just the sale of beer and wine. No taverns were called out by name, and the closest the paper came to describing the type of entertainment was a reference to "'cut throat competition' that made cabarets out of taverns." ("Waterbury Tavern Owners Bitter At Latest Ruling," Waterbury Republican, 7 July 1934, p. 2)

License Violations

Tavern and restaurant owners occasionally lost their liquor license for violating rules about what and when they could sell. In 1937, Paul Rechenberg, Jr., a Waterbury tavern owner, lost his license for selling liquor other than beer, while another Waterbury tavern owner, Charles Stankevicius, lost his license for keeping liquor other than beer with intent to sell. Peter Fardelli and Charles Fitzpatrick, Waterbury restaurant owners, lost their licenses for selling on Sunday before hours and without meals. ("Liquor Licenses Are Lost," Hartford Courant, 2 December 1937, p. 2)

The State Liquor Control Commission continued close supervision of taverns for decades. In 1949, for example, George Misunas, who owned a tavern at 883 Bank Street in Waterbury, had his tavern license suspended for 30 days after inspectors saw him selling whiskey to his customers. ("Two Taverns, Club Draw Suspension Of Liquor Permits," Hartford Courant, 27 October 1949, p. 9)

Speakeasies

The legalization of 3.2% beer and wine appears to have had little impact on the speakeasies in Waterbury. The Waterbury American speculated that most speakeasy operators would not be applying for permits, since it was draw attention to their liquor operations. On the first day of legal beer sales, Waterbury police arrested three people for public intoxication; all three were presumed to have gotten drunk on "bath tub gin." Beer drinkers interviewed by the newspaper agreed that the new 3.2% beer "was mild compared to the high-powered product of late years from wild-cat breweries." ("City Takes Its Beer In Mild Manner With Only Three Arrests," Waterbury American, 11 May 1933, p. 1)

The Waterbury American reported in July 1933 that the city's speakeasies were beginning to shut down, unable to compete with legal beer sales: "Some of the central speakeasies which thrived on gin and liquor sales and where fortunes were made are folding up rapidly, the receipts being so poor that expenses are not being maintained." ("Dime Beer in New Britain Again as Price War Ends," Waterbury American, 12 July 1933)

Despite the newspaper's claim that speakeasies were folding due to poor sales, they were still doing well enough for the Waterbury police department to launch a drive to shut them down starting in June 1933. The police "emergency squad" started by visiting "questionable establishments," instructing the owners to close up shop. Those who continued operation were subsequently arrested. Three violators were issued fines by the city court in July 1933: Vernon Holloman of 37 Vine Street was fined for operating a still and selling alcohol; Frank Gudasky of 225 Baldwin Street was fined for operating a speakeasy; and Joseph Galfota of 13 Congress Avenue was fined for operating a speakeasy. ("Three Convictions In Police Drive to Close Speakeasies," Waterbury American, 12 July 1933, p. 1)

Further arrests and convictions continued for months. Herbert Jetter of 230 Cherry Street was fined for operating a small liquor still in July 1933. Unable to afford the $50 fine, Jetter had to "work out the fine in jail." ("Court Fines Negro Still Operator $50," Waterbury American, 12 July 1933)

Charles Sprinks was arrested on July 13, 1933 on a charge of keeping liquor with intent to sell when the police emergency squad raided his speakeasy at 640 Bank Street. John Rubis was arrested earlier that week on the same charge when the emergency squad raised his speakeasy at 478 North Main Street. ("Charles Sprinks in Police Net," Waterbury Republican, 14 July 1933)

Ten people were arrested in raids on "disorderly houses" held on May 3, 1934. Rose Azzara of 133 North Main Street pleaded guilty to keeping liquor with intent to sell; she received a three months suspended jail term and six months probation. Azzara told the court she was a widow and had been selling the liquor to help support her four children. Her attorney informed the court that she would no longer need to illegally sell liquor, because three of her four children had recently gotten jobs. Capt. Daniel Carson, leader of the police vice squad, stated that Azzara's customers were primarily panhandlers who used the money they raised from begging to buy liquor from her. In addition to being placed on probation, Azzara was also ordered to move to a new home. ("Mrs. Azzara, One of Ten Arrested in Vice Raid, Pleads Guilty," Waterbury American, 3 May 1934, p. 2 and "Woman Gets Probation On Liquor Court" Waterbury Republican, 4 May 1934)

Taverns and Civil Rights

Connecticut's legislature passed a Civil Rights law in April 1933 prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, or creed with a penalty of $100 or imprisonment for 30 days or both. ("Civil Rights Bill Adopted by Senate," The Hartford Courant, 7 April 1933, p. 11 and "Civil Rights Bill Receives House Vote," The Hartford Courant, 14 April 1933, p. 3)

Less than two months after the bill was passed, the first violation was reported at a Hartford tavern on Village Street, which was charging 50 cents a glass to African Americans and only 10 cents a glass to anyone who appeared to be white. The Prosecuting Attorney refused to act on the complaint because the new law wouldn't go into effect until July 1. ("Tavern Accused of Discrimination Against Negroes," The Hartford Courant, 1 June 1933, p. 1 and "Prosecutor Refuses Negro Beer Case As Law Is Yet Pending," The Hartford Courant, 2 June 1933, p. 4).

A second instance of discrimination happened shortly after, at a tavern on Albany Avenue in Hartford. This time, the man trying to order a beer, M. W. Archer, was ignored while white people on either side of him were served. As with the incident at the Village Street tavern, no legal action could be taken because the new law had not yet gone into effect. ("Charge Tavern Refused Beer Sale to Negro," The Hartford Courant, 12 June 1933, p. 4)

Another instance of discrimination in a tavern happened in Waterbury in 1949, and it's that story which started me down this road of tavern research.

A series of articles in The New England Bulletin reported that Peter's Restaurant, also known as Pete's Tavern, was charging higher prices for beer to African Americans. The business was located on the corner of North Main and North Elm Streets in the North Square, which was by then a predominantly black neighborhood. The business owner, a French Canadian immigrant, lived in Wolcott. He opened his restaurant/tavern in 1946.

|

| Peter's Restaurant, a.k.a. Pete's Tavern, in the North Square The New England Bulletin, 30 April 1949, p. 1 |

The business owner, Peter Moisan, was charging ten cents per glass to whites and twenty cents per glass to blacks. When interviewed by The New England Bulletin reporter J. Edward Burke, Moisan offered up a number of excuses for charging blacks twice as much for their beer, from needing the money to pay for a television set to trying to discourage blacks from entering his business because most of his customers were white and "colors don't mix." (Eddy Burke, "Waterbury Bar Has 10-Cent Beer For Whites; 20-Cent Beer For Negroes," The New England Bulletin, 30 April 1949, p. 2)

Following Burke's exposé, Moisan began refusing service to blacks. A formal complaint was filed with the Connecticut Inter-Racial Commission and the cause was taken up by the Waterbury NAACP. An affidavit was signed by a white man, Walter Johnson, who testified that he had been charged only ten cents for his beer minutes after Burke had been charged twenty cents. (J. Edward Burke, "Pete's Tavern Now Bars Negro Trade," The New England Bulletin, 14 May 1949, p. 4)

In June, Prosecuting Attorney Albert Hummel issued a notice to Moisan that he was to serve black patrons without discrimination of any sort, or pay the consequences (J. Edward Burke, "Pete's Bar Warned On Beer Overcharge," The New England Bulletin, 18 June 1949, p. 2). This was a Civil Rights victory not only for the patrons of Pete's Tavern, but for tavern-goers throughout Connecticut.

So was this the Pete's Tavern of the token? Although the business's formal name was Peter's Restaurant, Burke repeatedly referred to it as Pete's Tavern. Beer was still ten cents a glass, so it's not impossible that the token was from this business, but I'm inclined to think that the token was from the 1930s.

Pete's Tavern

So which Peter issued the Pete's Tavern token? I still don't have a definitive answer to that question, but I have a pretty good guess.

I don't think it was Peter Moisan. His business was officially known as Peter's Restaurant, not Pete's Tavern, and it didn't open until 1946, which would be very late for this type of token.

The information I have on the other three Peters is as follows:

Peter Palapis was born in 1892 in Lithuania (then part of Russia), arrived in the United States in 1910, and became a U.S. citizen in 1926. He and his wife, Magdalene (Tamosaitis) Palapis, would eventually own several businesses on Bank Street in downtown Waterbury, where I-84 is now. The 1940 Census lists Magdalene as the owner of their cigar shop, and Peter as the owner of a tavern. The cigar shop was located at 321 Bank Street, which was also their home address, while the tavern was next door at 319 Bank Street. The tavern was in operation from 1933 or '34 until about 1950.

Peter Valunas was born in 1891 in Lithuania, arrived in the United States in 1910, and became a U.S. citizen in 1928. Before starting a tavern, Valunas ran a confectionery at 812 Bank Street in Waterbury's Brooklyn neighborhood, which was a predominantly Lithuanian community. He opened his tavern in 1933 or '34 at 776 Bank Street, also in the Brooklyn neighborhood, where Route 8 is today. The tavern remained in business until Valunas' death in 1943 or '44.

Peter Griffin was born in 1873 in Ireland. He lived on Fuller Street (where I-84 is now) in the Irish Abrigrador neighborhood. Before Prohibition, Griffin owned two saloons, one at 1528 Thomaston Avenue in the Waterville neighborhood, and one at 51 Fuller Street, on the ground floor of his multi-family house. During Prohibition, he operated a dry goods store at the Fuller Street address. It wasn't until 1939 that Griffin reopened his tavern. He continued to operate it until his death in 1948.

My best guess is that the token was issued by Peter Palapis during the 1930s, perhaps shortly after opening his tavern as an advertising tool. His tavern was in downtown Waterbury, and he and his wife owned several businesses, which suggests that they would have been inclined to spend some money on promotional giveaways.

|

| Pete's Tavern token, front and back -- possibly issued during the 1930s for a tavern in downtown Waterbury |

Peter Valunas' tavern presumably catered to the Lithuanian community in the Brooklyn neighborhood. While it is possible that he issued the token, I think it's less likely that a neighborhood tavern would pay for a promotional token. The least likely candidate is Peter Griffin, whose tavern reopened several years after Prohibition ended and presumably catered to a set crowd of neighborhood locals. But, since I don't know for certain, it could have been issued by any of the Peters.

Taverns and Women

When taverns opened for business on May 10, 1933, there was a fair amount of debate and confusion about the involvement of women. The new Connecticut liquor control legislation prohibited women from working in taverns, which raised a concern among hotel owners, who assumed the ban applied to any business serving beer. Thousands of women in Connecticut would have lost their jobs in hotels and restaurants if this were the case -- the Chairman of the Liquor Control Commission clarified that the ban on female employees applied only to taverns. ("Bergin Clarifies Two Disputed Sections Of Liquor Control Act," Waterbury Republican, 11 May 1933)

For some, the presence of women in taverns was horrifying. Waterbury's Lewis Lauria, former president of the State Liquor Dealers Association and secretary of the National Association of Beer, Wine and Liquor Dealers, was opposed to "the presence of women" in taverns. ("Tavern Ruling Rouses Wrath of Waterbury Man," Hartford Courant, 7 July 1934, p. 3)

For feminists, the new taverns were heralded as a modern advancement, where women, "with or without men," could enjoy a beer. Unlike the saloons of the era before Prohibition, taverns of the 1930s were brightly lit and inviting. "No longer need she speed past swinging doors, fearful lest some inebriated gentleman from the dimly yawning cavern beyond cross her path." (Julia Older, "Gone Are Taverns of Yesteryear," Hartford Courant, 10 September 1933, p. 61)

The tide began turning against Connecticut's drinking women in 1945. Liquor Commissioner and Hartford Republican Francis P. Rohrmayer submitted revisions of the State Liquor Control Act to the General Assembly. Among those revisions was a recommendation to ban women from taverns and from hotel and restaurant dining rooms in which liquor was sold at a bar. The proposed revisions also banned the sale of alcohol after 11 p.m. and on Sundays and were intended "to aid in the solution of problems relating to morals and health," which Rohrmayer claimed had "reached dangerous proportions." ("Liquor Law Changes To Be Submitted" Waterbury Republican, 16 January 1945, p. 3)

In 1949, the State Liquor Control Act was revised, banning women from drinking at bars in hotels, restaurants and taverns (General Statutes of Connecticut: Revision of 1949, Volume 2, pp. 1580-1581). The changes were pushed through by Rohrmayer with the support of the United Temperance Socities and various church groups. ("Rohrmayer Gives Liquor Suggestions," Hartford Courant, 16 January 1945, p. 1)

The law was further restricted in 1951, banning women from standing at bars even if they weren't drinking ("House Votes Sunday Bar Closing At 11," Hartford Courant, 1 June 1951, p. 14).

It wasn't until 1969 that the Liquor Control Act was revised to allow women to drink at bars so long as they were sitting at a table or on a bar stool ("Women Allowed to Sit at Bars as New Laws Go Into Effect," The Bridgeport Post, 20 September 1969, p. 49). The issue had been debated for years before the new law was passed. Those against allowing women to drink in bars said it "would create many problems and might create many embarrassing situations for permittees." Those in favor of allowing women to drink at bars noted that it would help Connecticut's businesses be more competitive, since the surrounding states allowed it. ("Committee Hear Views On Women at Bars," The Hartford Courant, 20 March 1965, p. 11)

Opponents to women drinking at bars also claimed that a woman who drank at a bar was often "no lady." Stanley J. Palaski, head of the State Liquor Control Commission, warned that allowing women at bars would lead to the presence of "B-Girls," women hired by the bar to encourage men to spend more money than they had planned on drinks for themselves and the B-Girl. ("Drinking By Women At Bars Opposed At Assembly Hearing," The Bridgeport Telegram, 1 March 1961, p. 2)

|

| B-Girl Decoy by Eve Linketter, published in 1961 |

Margaret O. Gray of the Women's Christian Temperance Union of Connecticut declared that serving women at the bar would return the state to the bad old days of saloons, implying all sorts of misbehavior would be involved. Waterbury's Edward M. Ryan echoed Gray's sentiment, saying that the law should be left unchanged to "prevent the return of the old-time saloon." Another Waterbury resident, Harmon A. Genlot, who was spokesman for the Connecticut Restaurant Association, warned that there were many "run-of-the-mill" restaurants with low standards. ("Drinking By Women At Bars Opposed At Assembly Hearing," The Bridgeport Telegram, 1 March 1961, p. 2)

When the law was finally passed, some bar owners threatened to remove the stools from the bars, since women were required to be sitting down while drinking ("Cafe Bill Vetoed," Hartford Courant, 6 July 1969, p. 41).

Two years later, the Connecticut Human Rights and Opportunities Committee pushed for the law to be revised to allow women to stand at bars. Men who didn't want to share the bar with women had reportedly been swiping the women's bar stools, forcing them to stand at the bar, which was not legal. "Longer Bar Hours Backed With Women Standing Up," The Bridgeport Post, 11 March 1971, pp. 1 and 10)

Joe Begnal, then president of Waterbury's Full Liquor Permit Association, was accepting of letting women drink at bars, which he saw as being part of a movement for greater equality for women. ("Bill Unopposed On Drinking At 18," The Bridgeport Post, 18 March 1971, p. 51)

The new revision to the Liquor Act was signed into law by Govenor Meskill on May 18, 1972 and went into effect on October 1, 1972 ("Women Can Stand At Bars In State Starting Oct. 1," The Bridgeport Telegram, 19 May 1972, p. 23).

Taverns Today

Although a bar might call itself a tavern, if it sells cocktails, it's not technically a tavern in Connecticut. A search of the state's license database pulls up approximately 72 active tavern licenses, but these don't necessarily fit the traditional concept of a tavern. For example, Apple Cinemas in Barkhamsted has a tavern license.

A tavern license is $400 per year, while a liquor license for a restaurant is $1,550 and a liquor license for a hotel in a city with a population of 50,000 or more is $2,750 per year. The tavern license is the least expensive option for limited sales of alcoholic beverages (beer and wine).

In Waterbury, there are three businesses with a tavern license: Vincenzo Pizzeria on Highland Avenue, Banana Brasil Grill on South Main Street, and Benevento Caffé on North Main Street.

Absolutely fascinating article!

ReplyDeleteThank you!

I agree, it was fascinating!

ReplyDeleteWhether they're called taverns or not, neighborhood bars seem to be somewhat of an endangered species in the US today. Their numbers are on the decline.

Peter

I love your article. It goes into the history of Waterbury and taverns. I recently published a catalog of Connecticut Trade Tokens in which I list this token but I was not able to attribute it to any one proprietor. It is definitely, based on the design, Post-Prohibition. If you wish to discuss this token further, you can contact me at connecticuttokens@gmail.com. Great work.

ReplyDeleteManuel A. Ayala

I recall my now-deceased father speaking of a Petey Polletta's Tavern in the North End. Probably somewhere around North Main. I'm almost sure that was the name he said. Apparently, my two grandfathers used to go there - it would have been in the 1940's.

ReplyDeleteThat was amazing, thank you so much for putting in the time

ReplyDeleteI grew up in the waterbury area my father roy mcdermott won the mustache of the year award he used to talk about a bartender named Richard mcdermott he is related to me

ReplyDelete