Every high school U.S. history class includes at least a mention of “Bleeding Kansas,” the conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces that took place during the 1850s. The legendary John Brown established his reputation for violence during the conflict and is closely associated with the bloodshed that happened there. It turns out there were a number of Waterbury people in Kansas at this time, including some who were directly involved in the conflict. Two of those Waterburians, William Chestnut and Henry Barlow, sent a series of letters to the Waterbury American newspaper, giving first-hand accounts of what was happening in Kansas. Their letters give a perspective on the conflict that is missing from the textbook accounts of what happened, and they give us a sense of how the conflict was viewed in Waterbury.

|

| A symbolic image of John Brown and Bleeding Kansas "The Tragic Prelude" mural at the Kansas State House, painted by John Steuart Curry in 1942. |

The Politics Behind the Conflict

As the United States expanded its territory westward, abolitionists tried to stop the expansion of slavery into new states. Free states and slave states struggled for political dominance in Congress, with slavery states pushing through legislation to ensure that wouldn't be outvoted by abolitionist politicians.

The Three-Fifths Compromise of 1787 allowed slave states to increase their allotted number of representatives by counting enslaved people as part of their total population, even though they had no rights of citizenship. The "compromise" was to use only three-fifths of the enslaved population total instead of the full total in an effort to maintain an equal share of power between free and slavery states in Congress.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 established guidelines to maintain the balance of free states and slavery states in the Senate. Maine was admitted as a free state, while Missouri was admitted as a slavery state. The compromise also established that any new states established above the 36º30' latitude would be free states.

The compromise fell apart in 1854, when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, repealing the Missouri Compromise and allowing every new state to decide for itself whether or not slavery would be legal. Kansas and Nebraska were the next two territories expected to become states. Under the Missouri Compromise, they would have been free states. With the repeal of the compromise, it became possible that both would become slavery states.

Passage of the bill was largely the work of U.S. Senator David Atchison of Missouri, who wanted to repeal the Missouri Compromise so that slavery could be expanded to more territories. Atchison and his family were wealthy plantation owners. The 1860 Census listed sixteen people enslaved by Atchison, ranging in age from 3 to 48. Atchison's widowed sister-in-law, who lived on the same plantation, kept an additional ten people enslaved.

Atchison had a deeply-rooted hatred of abolitionists. His motivation for striking down the Missouri Act was to prevent the creation of a Free State next to Missouri. He gave numerous speeches warning that "Negro stealing" by abolitionists would ruin Missouri, and recommending that "negro thieves" should be hanged. Atchison appeared to be unwilling to believe that enslaved people might decide for themselves to escape slavery. ("Senator Atchison on Kansas," Albany Journal, 1 December 1854, p. 2)

|

| Map showing impact of Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 (McConnell Map Co., 1919 - Retrieved from Library of Congress) |

When the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, the Waterbury American declared that "Slavery has triumphed over freedom." Three congressmen from New England voted in favor of the new law, including one from Connecticut, Colin M. Ingersoll of New Haven. Connecticut's other three representatives all voted against it. ("The Nebraska Bill Passed," Waterbury American, 26 May 1854, p. 2)

The Kansas-Nebraska Act created a free-for-all rush to settle the new territories. Kansas, located next to Missouri, was the focus of anti-slavery efforts, since its proximity to a slavery state made it more likely to become another slavery state.

The Native Americans living in the two territories had previously been promised that the land would remain theirs. Senator Sam Houston of Texas argued on their behalf, ashamed that the U.S. would ignore established treaties, but the majority of Congress had little interest in allowing Native Americans to retain their rights to their land. ("Speech of Hon. Sam Houston," Hartford Weekly Times, 4 March 1854, p. 1)

William Chestnut

William Chestnut and his family were among the first emigrants to settle in Kansas following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. William and his wife, Mary (Barbour) Chestnut, and their oldest children were all born in Scotland, moving to the United States and Waterbury in 1842. William worked as a laborer in Waterbury's factories. In 1854, when they moved to Kansas, William and Mary were in their late 30s. Their oldest children were teenagers.

The Chestnut family moved to Kansas with a group of emigrants on trip arranged by the Kansas League, a New York City based organization created to support "free soil emigration." There were numerous emigrant aid organizations that were created during this time, all with the goal of sending enough anti-slavery settlers to Kansas to ensure that the territory would become a free state.

The New York Kansas League advertised for settlers to travel as a group, promising to help them at every step of their journey. The Chestnut family left from New York City on October 3, arriving in Kansas on October 15.

|

| Advertisement for train to Kansas, New-York Tribune, 26 September 1854, p. 1 |

William Chestnut wrote a letter to his Waterbury friends on December 18, 1854, letting them know what had happened since he and his family left. Chestnut was filled with optimism and encouraged "all the friends of freedom" to join them. The letter was printed in the Waterbury American on January 19, 1855.

Dear Friends--I am happy to inform you that we are all in first rate health, and have been so since we left Waterbury. We had beautiful weather all the way out here, and enjoyed the excursion very much. We arrived in St. Louis Sunday, Oct. 8th, and got on board of a splendid steamer about 2 p.m., where we found everything necessary for our comfort and accommodation--the boat was fitted up in the style of first class hotels, and we were shown the greatest attention and kindness by all the officers on board, even including the slaves, who waited on the table. We did not sail until Tuesday night, at 12 o'clock. I could write a whole week on the pleasure we enjoyed going up the Missouri--the scenery is beautiful beyond description. As we steamed along, we saw men at work in several places on the great Pacific Railroad. They are pushing it along with all expedition possible.

|

| Steamboats docked at the St. Louis Levee, 1853 Missouri History Museum Photographs and Prints Collections. Thomas Easterly Collection. N17007. |

We got to Kansas [Kansas City] Oct. 15. There we found a small, dirty, mean-looking city, overrun with pigs and dogs; the houses looked so nasty and shabby, one would have supposed the quadrupeds to have been the sole occupants. We were told when we left New York, under the auspices of the Kansas League, that when we got to Kansas we would find one of their agents, who would give us all the information we would require. We however, found no agent, he had gone into the Territory, and no one knew anything farther about him.

|

| Kansas City Riverfront, 1853 Collection of Kansas City Public Library |

Chestnut gave a long, detailed description of Kansas, emphasizing the natural riches to encourage more settlers to join him.

We forthwith held a meeting, and resolved to provide for ourselves. We sent out a committee to explore, and the rest of the company agreed to stay in Kansas until they would return and make a report. There were about forty of us, altogether, from all parts of the States. When the committee returned they recommended two places--some went to the one, some went to the other. We have settled in a beautiful country in the south part of the Territory, in what is called the Pottawattamie country, on the head waters of the Osage River, right between the Pottawattamie creek and the Marydesigne [Marais des Cygnes]--they come together at this place, forming the Osage. The prairie is about a mile wide for about five miles above the forks, with a heavy strip of bottom timber on each side, so that it conveniently divides into farms, giving each one prairie, timber and water. The soil is a rich black loam, underlaid with light clay and limestone. We have sand, gravel, sandstone suitable for grindstones, the best of clay for bricks, water as clear as crystal, and plenty of it. Our timber consists of white walnut, black walnut, pig walnut, burr oak, post oak, hackberry, mulberry, &c. &c. We have got all the business men and men of capital of our party with us. We call our settlement Osawattamie. We have a gentleman with us from Rochester, N.Y., who has commenced erecting a steam saw and grist-mill on a large scale; he is going to open a large store in the Spring. We are now fifty miles from any post office or trading place, but we have all the elements of a prosperous village within ourselves. We have capital, energy, strong arms, and willing hearts.-- We will make our mark on the early settlement of Kansas.

It is one of the most beautiful countries I ever saw--the climate is all that could be desired. We have had only one day since we came here that we found disagreeable to work out doors--think of that--and this the 12th day of December, ye poor shivering ones of the land of "wooden nutmegs!" We have grass now as green as ever in our timber lands. I bought two yoke of oxen and a large covered wagon for $182. My cattle are now plump and fat as ever--we don't feed them at all. I bought a tent, tools and provisions, started with John, William [Chestnut's teenage sons] and some members of our company, and left the rest of my family in Kansas [City]. In one week, with a little assistance, a log cabin was got ready. So I started for Kansas and brought my family, where we have been now over six weeks. My wife likes our new life a great deal better than she thought she could--she is a great deal fatter and healthier looking, and so are all the children, than when we left home. I feel confident that this is the best move I ever made in my life. I think I see before me a certainty of a future glorious independence--and I think any one with ambition above being an understrapper, and with limited means, cannot fail to better his condition by coming out here.

We want all the friends of freedom, who wish to emigrate, to come here with their free speech and free labor. Their industry will be better rewarded than in any other part of the States. We have some settlers here from Iowa, and other western states, who say this country has advantages over any other part, and people ought to know it. I think some of the squatters could be bought out in the Spring for from $150 to $200, with good timber, water, &c., &c. We have bituminous coal within two miles of us, and we have an opinion that this part of the country will soon be thickly settled. The timber claims will mostly all be taken up in the Spring, but coal and stone are in abundance, and will induce settlers to come to our beautiful rolling prairies.--We have no stagnant water here whatever--the land is all gently rolling, with small ravines every little distance, leading to the creeks and river.--The banks of our streams are very high. From five to ten miles apart we have some very high hills, from two to five hundred feet in height, with frequent springs of water on their tops and sides--this variety gives a beautiful appearance to the country.--We have pleasant social evenings in our log cabin, and beguile the time by playing on our instruments, the beautiful melodies of Christy, Campbell, Bulkly, &c., &c. We ask no special favors, but try to deserve success, though we may not command it. "God for the right."

Yours as ever, Wm. Chestnut.

Chestnut gave more details about their trip west in his second letter, written on February 5 and published in the Waterbury American on March 2, 1855:

I left Waterbury, Oct. 2d, 1854, under the auspices of the "N. York Kansas League," and embarked from N.Y. Oct. 3d, at eight p.m. We were furnished with through tickets to St. Louis, for $22, where we arrived Oct. 8th. We there found a steamer bound for the upper Missouri, and sailed Oct. 12th, at 12 p.m. Steamers can generally be found there three or four times a week going up, landing passengers at some half dozen small towns between St. Louis and Kansas, the fare generally ranging from $4, to $10 per passage, children half price, board always included. The boats are fitted up in the style of our first class hotels, and we fared like princes. We were allowed one hundred lbs., baggage per passage all over, at a charge of $1 per hundred from St. Louis. We were joined by a number from Rochester, and other points along our line of travel, so that when we landed at Kansas we numbered about 50 including four families and 12 children.

Chestnut advised men with families to leave their families in one of the established towns on the Missouri River until finding a home lot. He also gave practical advice about the price of flour, meal, beef, and pork to help emigrants plan their budget. He ended his letter with a personal note about his experience and an invitation for the general public to write to him with their questions.

I would say to those who may be afraid of a pioneer life, that until I left Waterbury, I had never worked one whole day out of doors in my life--yet I get along first rate, and enjoy myself better than I ever did before. We all enjoy first rate health and think our coming here will be very much to our advantage. And I will conclude by stating that if any of your readers or my acquaintances should wish any further information with regard to this Territory, I will very cheerfully answer any enquiries addressed to me at the earliest opportunity.

Chestnut's second letter also included a little information about the people who lived in Kansas before the white settlers arrived, as well as information about the other settlers. As before, Chestnut wrote with enthusiasm and optimism, believing the best of everyone he encountered.

There are a great many coming in here from all parts of the Union--I have talked with several from Texas and Iowa, who state that this country is far ahead of either of those two States for stock raising or for general good health and beauty of scenery.--We find the Indians very friendly, and life and property are quite as safe here as in Waterbury, though surrounded with Pottawattomies, Peories, Piankishaws, Sacs, and Foxes, and Shawnees, they never trouble us, in fact they keep out of our way so that we seldom see them. One gentleman of our party has started for the states to have a plan for a town plot lithographed, and we flatter ourselves that we are going to have all the advantages of civilization here in a very short time. Our settlers for miles around are all sober, industrious and law abiding citizens, and go in heart and soul for having this a free State. I am personally acquainted with a number of settlers from several of the slave states, who say they will vote for freedom, they seem to think with the poet:

"That freedom hath a thousand charms to show

That slaves howe'er contented ne'er can know."

|

| Sac and Fox Bark House, c. 1850-1870 Kansas Historical Society |

Pro-Slavery Voter Fraud

Despite Chestnut's optimism about Kansas becoming a free state, pro-slavery men from Missouri were determined to make Kansas a slave state. During the territory's first election on November 29, 1854, Missouri men crossed into Kansas to vote illegally for the pro-slavery candidate for U.S. Congress. "Border ruffians" from Missouri threatened violence against Kansas Free State voters and election judges. More than half the votes cast were illegal, but an effort to challenge the results was unsuccessful. Missourians successfully repeated their voter fraud on March 30, 1855, when the first Kansas legislature was elected, all pro-slavery.

William Chestnut was one of the election judges on March 30, charged with overseeing his district's polling place, located at the home of Henry Sherman (known as "Dutch Henry"). When a "noisy, drunken mob" from Missouri showed up on horseback to vote, Chestnut tried to prevent them from voting as they were not Kansas residents. The mob threatened violence, and local officials warned Chestnut to back down. Free State men left for their own safety, while others never made it to Dutch Henry's house, turned away by pro-slavery Kansan James Doyle and his sons. (S. J. Shively, "The Pottawatomie Massacre," Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society, Vol. VIII, p. 178)

The Missouri mob "elected" a pair of judges to replace Chestnut, who had been appointed to the position by the Governor. The judges allowed the Missourians to vote without being sworn in, but they still needed Chestnut's signature to certify the returns. Chestnut refused to sign despite being threatened with violence, and ultimately left the polling place. He estimated there were three times as many illegal votes to legal votes in the election. As he returned home, he was shot at by Missourians, but escaped injury. (U.S. House of Representatives, Report of The Special Committee Appointed to Investigate the Troubles in Kansas. Washington: Cornelius Wendell, Printer, 1856)

|

| Voting at Kickapoo, Kansas, 1857 Illustrated in Albert D. Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi, 1867 |

The new, illegally-elected, pro-slavery legislature, nicknamed the "Bogus Legislature," swiftly ousted all Free State legislators and relocated the new capitol to the border with Missouri. A highly punitive pro-slavery law was passed in August 1855. The Act to Punish Offenses Against Slave Property included the death penalty for anyone helping enslaved or free Black people in a rebellion or insurrection, either the death penalty or ten years' hard labor for assisting fugitive slaves from other states, and felony charges for speaking, writing, or sharing information against slavery. The law also banned anyone opposed to slavery from serving on a jury.

Free State Kansans refused to recognize their new legislature as legitimate. They set up their own government and tried to have Kansas admitted to the Union as a Free State. They gathered at Topeka in October and November 1855 and drafted a constitution that prohibited slavery. In a compromise to racist Free State settlers, the constitution also prohibited free Black people from settling in Kansas.

The Free State convention attendees elected a governor, Charles Robinson, and legislature for Kansas, but they were not recognized by the United States as legitimate. The official pro-slavery government threatened to arrest Robinson and his legislature "immediately upon taking the oath" of office, but did not follow through on that threat until the following year. (William Chestnut, "From Our Kansas Correspondent," Waterbury American, 18 April 1856, p. 1)

Border Ruffians and Sharps Rifles

Tensions were increasing between Free State Kansans and pro-slavery "border ruffians" from Missouri. One of the most visible leaders of the border ruffians was David Atchison, the wealthy pro-slavery plantation owner who was a Missouri U.S. Senator from 1843 to 1855. Atchison actively promoted violence, up to and including lynching, to stop abolitionists from settling in Kansas, using fear-mongering tactics to gain support from Missourians.

|

| Two unidentified Border Ruffians with swords Blackall, photographer, Clinton, Iowa Retrieved from Library of Congress |

At a public speech on September 21, 1854, Atchison urged pro-slavery squatters in Kansas and Missouri to lynch abolitionists, telling them that they should "hang a Negro theif [sic] or Abolitionist, without Judge or Jury." He received "almost universal applause." In a letter to Jefferson Davis, who was the U.S. Secretary of War, Atchison stated that he was organizing an anti-abolitionist movement and was prepared to "shoot, burn & hang" any anti-slavery settlers who came to Kansas. Both Atchison and Davis had been influential in passing the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. Atchison stood to profit if Kansas became a slave state. Furthermore, his prosperity as a plantation owner was threatened by the close proximity of the Underground Railroad in Kansas. As Secretary of War, Davis advised President Pierce to side with the pro-slavery forces in Kansas. (Letter to Jefferson Davis, September 24, 1854, The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Vol. 5, 1853-1855. Louisiana State University Press, 1985; Eugene T. Wells, "Jefferson Davis and Kansas Territory," The Kansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1956)

|

| Mathew Brady daguerreotype of David Atchison Library of Congress |

Atchison led a large band of border ruffians in a volunteer military company, raiding northern settlers of Kansas numerous times. He convinced his followers, and many Southerners, that "the cause of Kansas is the cause of the South." In his view, if Kansas became a Free State, Missouri would no longer be a Slave State, and he preached that "the prosperity or the ruin of the whole South depends on the Kansas struggle." ("The Apostle of Squatter Sovereignty in Kansas--Letter from Atchison," Albany Journal, 3 November 1855, p. 2)

Believing themselves to be on the side of good, protecting the South from abolitionists, the border ruffians were free to commit whatever acts of violence they wished, supported by some of the most powerful men in the country.

An anonymous "sermon" published in The Kansas Herald of Freedom on March 24, 1855 declared the "proper time also to kill Abolitionists is whenever they presume to settle in the newly organized Territory of Kansas. I am happy to find my sentiments adopted, and eloquently avowed by the Honorable U.S. Senator Atchison. In a speech recently delivered in that Territory, he said, that, if he had his way, he would hang every Abolitionist that dared to show his face there."

After experiencing recurring violence from the border ruffians, and continuing to hear the threatening rhetoric from Atchison and others, Free State Kansans were motivated to take up arms in their own defense and began forming military companies for the purpose. The thousands of violent Missourians who mobbed the polling locations on March 30 proved to be a wake-up call for many Free Staters.

Charles Robinson, the future Governor of Free State Kansas, was also the Kansas-based agent for the New England Emigrant Aid Society. He wrote to the president of the society in Massachusetts on April 2, 1855, telling him about the violence and fraud he witnessed during the March 30 election. Robinson asked for rifles to be sent for the new Free State militias:

Give us the weapons & every man from the north will be a soldier & die in his tracks if necessary to protect and defend our rights. It looks very much like war & I am ready for it & so are our people. If they give us occasion to settle the question of slavery in this country with the bayonet let us improve it. What way can bring the slaves redemption more speedily - Wouldn’t it be rich to march an army through the slave holding states & roll up a black cloud that should spread dismay & terror to the ranks of the oppressors? But I must close, for want of time - Can not your Secret Society send us 200 of Sharps rifles as a loan till this question is settled? also a couple of field pieces? – If they will do that I think they will be well used & preserved. (Charles Robinson to Eli Thayer, Kansas Memory Website)

|

| Sharps' Rifle Manufacturing Company Advertisement, c. 1855 Kansas Historical Society |

Life at Osawatomie

The Chestnuts and the other settlers at Osawatomie celebrated their one-year anniversary on October 24, 1855 with "a first rate dinner" and a review of their "pioneer experience" in that first year, which he wrote about in a letter on October 27, published in the Waterbury American on November 23, 1855:

We all had several very amusing and interesting reminiscences to recount which made the occasion one of unusual interest, especially so as all were highly pleased with the results of squatter life, with the land of their adoption, with its climate, productions, &c.--And above all with the bright, glorious future that we all thought we could see and very shortly realize for ourselves and families.

The first year was not without daily hardships, despite Chestnut's positive outlook. Sickness and death had visited the small settlement, and his own family had been sick for two months. Chestnut wrote that they had expected sickness, "as it is common in every new country... a kind of initiation fee which we all have to pay for the good time coming." While Chestnut and his family were severely ill, "we did it as cheerfully as possible." For the members of the settlement who died, Chestnut assured potential emigrants that there was nothing to fear, for the deaths "could be traced to some very great indiscretion on the part of the deceased."

Chestnut expressed a negative view of a certain type of settler, writing that "a great many come out here who never ought to have left home. They come entirely destitute of means and nearly as destitute of energy or enterprise, get a little sick, become home-sick, return; and in order to account for their want of success and as an excuse for their general shiftlessness, they abuse and misrepresent the country, and have been the means of materially diminishing the immigration from the east."

Chestnut vigorously defended his new home against rumors of hardship and danger, "that this land is swarming with rattlesnakes, half savage Indians, drunken Missourians, &c." He insisted that he had never lived anywhere better or safer (making no mention of what happened to him at the election), that "we have very few snakes, the Indians are no trouble whatever, and the Missourians only at election times."

Chestnut was certain that Kansas would become a free state, that there was no chance of it become "slave territory, the result of the late pro-slavery election to the contrary notwithstanding." He placed his hopes in the Constitutional Convention being held at Topeka, firmly believing that "the 'sum of all villainies' can never blast the energies or mar the prosperity" of Kansas.

As for the "pro-slavery propagandists" in Missouri, Chestnut wrote "they will find that the spirit of the age is against them and if this has no effect upon their seared consciences they will find plenty of Sharp's rifles with steady hands and sure eyes that will bring them to a sense of their situation. The settlers here will only live as freemen in a free state let the consequences be what they may; mark that."

John Brown

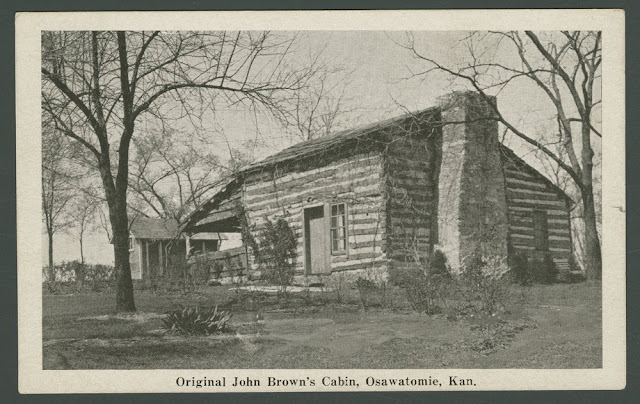

Chestnut's neighbors at Osawatomie included Rev. Samuel L. Adair, a few years older than Chestnut, who was married to Florella Brown, sister of John Brown. The Adairs traveled to Kansas with the New England Emigrant Aid Company, building a log home for their family in Osawatomie in 1855. The Adair cabin is believed to have served as a station on the Underground Railroad.

|

| Adair Family home, postcard view, c. 1912-1927 Collection of Kansas Historical Society |

John Brown arrived in Kansas in October 1855 with his teenage son, Oliver, and his son-in-law, Henry Thompson. Several of Brown's other sons and their wives had settled near Osawatomie, naming their settlement Brownsville. Brown stayed with his family at Brownsville, visiting the Adairs regularly. His first concerns upon arrival were practical, reviewing the crops and livestock that would support his family, expressing concern for his family's poor health, and updating his father about how things were going. Like William Chestnut, Brown was optimistic that the Free State Kansans would win out. (See John Brown letters, Ohio Memory website and The Life and Letters of John Brown, edited by Franklin B. Sanborn)

|

| John Brown, photographed in 1856 or 1857 Collection of Kansas Historical Society |

Coming Up Next: The Sack of Lawrence, Pottawatomie Massacre, Raids on Osawatomie, and Henry Barlow is (nearly) Lynched

No comments:

Post a Comment