First, some background:

The Lewis Fulton Memorial Park was donated to the City of Waterbury in the 1920s. The land was purchased by Fulton's parents in 1919. His father, William E. Fulton, was president of Waterbury Farrel Foundry and Machine Co. and lived at 150 Hillside Avenue.

[

Correction, 4/8/2019: Ida E. and William Edwards Lewis donated the land for the park in two separate parcels in 1918. The first was a parcel containing 36 acres, which was offered to and accepted by the Board of Aldermen on February 1, 1918. The second was a parcel of 3 acres which was offered to and accepted by the Board of Aldermen on March 4.]

Lewis Edwards Fulton died in 1917 at the age of 38. He had been the treasurer at Waterbury Farrel until 1913, when his brother took over. According to his obituary, published in the 1917-1918

Obituary Record of Yale Graduates,

Lewis Fulton

suffered from a debilitating illness which forced him to resign from

the family business (Waterbury Farrel). From 1913 until his

death in 1917, he lived with and was cared for by his parents.

I have not found any specific information about the disease Fulton suffered from--back then, it was terribly impolite to discuss something as personal and as unpleasant as a fatal illness. Today, of course, we know that fostering awareness goes a long way toward fighting diseases, and can help improve the quality of life for people suffering from health problems. What a testament, however, to the love of parents for their child, that

Lewis Fulton's father paid for such a beautiful public memorial to his long-suffering son.

The park's Registration Form with the National Register of Historic Places is

available online in PDF format, and the supporting images are also

online in PDF format (large file, about 6 MB).

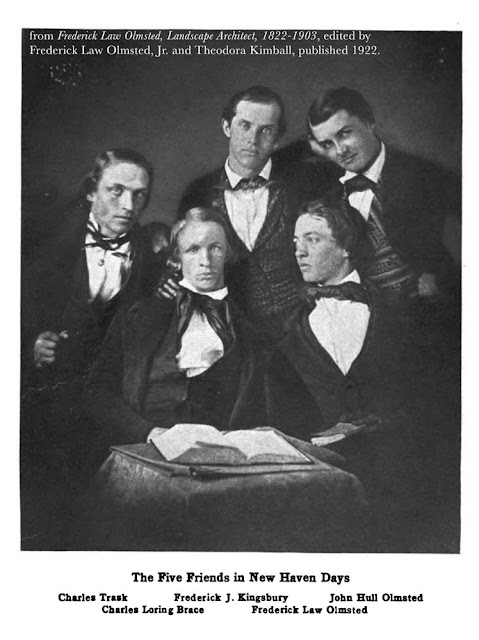

The Olmsted connection to Waterbury goes back to the 1840s. Frederick Law Olmsted, who eventually became the famous landscape architect, was a close friend of Frederick J. Kingsbury, whom he met while they were both students at Yale. Kingsbury later married into the Scovill family and became president of Scovill Manufacturing. Thanks to the connection with Kingsbury, Frederick Law Olmsted came to Waterbury in 1845 to

study agriculture on the farm of Joseph Welton.

In the 20th century, Olmsted's sons took on many projects in Waterbury, including Fulton Park. They also designed Library Park with Cass Gilbert in the 1920s and numerous other parks and private properties.

The finding aid to the

Olmsted Associates papers in the Library of Congress lists the "Waterbury Common" as a 1906 job. Other listed jobs and correspondence in Waterbury include William H. White (1917), Chase Companies (1919-20), Chase Park for Frederick S. Chase (1919-1921), Library Park (1919-1949), Henry L. Wade and J. S. Dye (1920), Waterbury Hospital (1920), Edward O. Goss (1920), Fulton Park (1920-24), Hayden Homestead Park for Mrs. William S. (Rose Hayden) Fulton (1920-21), Fairmount Subdivision for Chase Companies (1920-21), North Main Street project for Chase Companies (1921), Charles H. Brown (1921), Frederick S. Chase's burial lot at Riverside Cemetery (1921-23), A. C. Swenson (1924-29), Bartow Heminway (1926-46), Church of the Immaculate Conception (1928), H.S. Coe (1928-1937), First Congregational Church (1928), Country Club Homes, Inc. for Charles Sherwood (1929), Richardson Bronson (1929-30), I. W. Day (1930-1950), Calvary Cemetery (1932-33), Bunker Hill Improvement Association (1944-45). I have no idea if all those projects were completed. In addition, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. designed the WWI federal housing project on Laval, Lounsbury, Welles and Madison Streets.

Now, the greenhouse:

A former and hopefully future gem of Fulton Park is the greenhouse. Just as the City Hall building was allowed to deteriorate over the years, the greenhouse has been neglected. More than neglected. It's completely abandoned.

A greenhouse like this could be a tremendous asset to the city. It could even generate revenue--many greenhouses have flower shows in the middle of winter and they are always very popular. The greenhouse could also be used to grow plants for sale to help support the care and maintenance of the park. At this point, however, the greenhouse is unusable.

Many people are upset that the city has allowed the greenhouse to fall apart, but as I am learning, this is pretty typical for how the city has operated for many years. The city infrastructure is falling apart everywhere. Sidewalks are crumbling apart, buildings are falling apart, and the city has no program in place for keeping things from falling apart.

The city is dependent upon state and federal funding for repairing things when they fall so far apart they can no longer be used. Funding has come in for the greenhouse--it has yet to be used for the greenhouse.

The state

Bond Commission approved $250,000 specifically for the greenhouse in 2008, adding to $150,000 secured by State Senator Joan Hartley

a few years earlier. Going back further, in 2004 Waterbury received $350,000 from the state to renovate the greenhouse as well as finish some repairs to Hamilton Park's basketball and tennis courts, swimming pool and baseball field (

Rep-Am, January 31, 2004). That's close to half a million dollars of state money that has been funneled to Waterbury for a project that has yet to happen.

William Fulton created a trust fund for Fulton Park in May 1923. Following his death in 1930, the fund was given to the city, at which point it was estimated to be worth about a quarter of a million dollars. If that fund had been well managed over the decades since then, it would be quite sizable, generating more than enough money to keep up Fulton Park. I don't know anything about what has happened to the fund since 1930, but I suspect there's not much left. Finding out what happened to it could be very interesting.

The brick house in front is a lovely building and looks like it's structurally sound and relatively easy to fix up. There is a matching brick structure at the opposite end of the greenhouse. The architectural details are refined and complex, the sort of thing you don't see in modern buildings.

The greenhouse sits on a rustic stone foundation that looks very much like the other Olmsted-designed buildings in the park. The cinder blocks on top of the foundation look like something that would make the Olmsteds scream in horror. As you can see from the photo below, there's also a doorway that's been filled in with cinder blocks.

The framework of the greenhouse is rotted out and most of the glass is broken (be careful walking next to the building, the ground is layered in broken glass hiding in the grass).

The interior looks like something from a horror movie about a haunted house.

Below is a detail showing the name of the greenhouse's manufacturer, the American Greenhouse Mfg. Co. of Chicago. They were very active around 1920, when Fulton Park was being built.

The American Greenhouse Manufacturing Co. advertisement from the September 1919 issue of

House and Garden magazine, and another of their ads from the August 1919 issue of

Garden and Home Builder magazine, show greenhouses very similar to the one at Fulton Park.

This suggests that at least part of the greenhouse is original. It's not impossible for there to have been cinder blocks originally. I can't tell from the ads how the AGMCo greenhouse foundations were constructed.

The next photo shows part of an addition to the brick building in the back of the greenhouse. On the right of the image you can see the cinder block addition, possibly from the 1950s.

Here's another shot of the addition, showing its very faded NFPA Diamond hazard signage.

The

Connecticut Post ran an article by Ken Dixon about the state's growing deficit on February 21, 2010, criticizing the state funding of projects like the Fulton Park greenhouse. Dixon wrote "How about the new $250,000 greenhouses at Waterbury's Fulton Park? Some of those geraniums are yours." Imagine what he might have written had he known that the figure is over $400,000 and none of it has been spent on the greenhouse.