For the first part of this story, read Bleeding Kansas, Part One

-------------

On March 28, 1856, William Chestnut wrote a letter to the Waterbury American

"to apprise your numerous readers of the progress of events in this

part of the world." Winter was over, and most of his neighbors had

recovered from the "chill and fever" that ran through their community.

Plowing the fields and planting the crops had begun, "and we will soon

make the wilderness blossom like the rose." ("From Our Kansas Correspondent," Waterbury American, 18 April 1856, p. 1)

Chestnut assured his readers that "the actual settlers" would never be driven out by the Border Ruffians and were willing to die rather than back out. He spoke only generally about ruffian activities: they "have already desecrated our lovely plain with their drunken, ribald orgies; our virgin soil has already been stained with the blood of American citizens for the crime of attempting to exercise their rights as freemen--the right of self-government."

Chestnut was nearing the end of his willingness to peacefully endure the harassment and violence of the Border Ruffians, saying "there is a point beyond which endurance becomes a crime--we have hitherto acted on the defensive only, but when our present arrangements are completed we may be prepared to carry the war into Africa, should it be forced on us."

He gave an

example of the sort of thing which the Free Staters had to endure,

highlighting the level of distrust and disrespect between the two

factions:

The ruffians have an organization at Lexington [Missouri], on the river, where they board every boat coming up and forcibly detain them until they examine their freight list. One of our townsmen, a few days ago, had a very fine piano come up, and as it was boxed up very strong, it at once excited the suspicions of the ruffian horde--it was "Sharp's rifles," said they, "and no mistake," though they were shown the invoice and were assured it was only a piano--but all to no purpose. They dispatched a deputation to go up to Kansas City and watch the debarkation of the object of their suspicion, and as soon as it was put ashore, they insisted on having it opened. The person having it in charge accordingly took out all the screws and undid all the fastenings, until he came to the last screw, when he invited the ruffians to finish the job and raise the lid themselves--but they shrank back and refused to touch it, swearing that it was a Yankee trick to blow them up; that it was full of torpedoes, they knew, and proposed throwing the box into the river, saying it would serve the d---d Yankees right. This was as far as it would do to carry the joke, and the lid was accordingly raised amidst a general laugh of a large crowd who had collected on the occasion.

|

| Lexington Landing, Missouri, 1861 Retrieved from House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College |

During the mid-1850s, there was a brief-lived Waterbury Democrat newspaper (completely unrelated to the Waterbury Democrat which began publication in 1887). The Democrat, as the name implied, was a partisan newspaper, promoting the viewpoints of the Democratic party, which in 1856 adopted a platform of limited government, territorial expansion, and an insistence that Congress had no right to interfere with slavery, criticizing abolitionists for their efforts, even as they praised the Declaration of Independence for making the United States "the land of liberty and the asylum of the oppressed of every nation."

The Democrat was, in Chestnut's words, "of the subterranean border ruffian stamp," a "mouth-piece" for pro-slavery politicians. The newspaper ran an editorial titled "Kansas Lies," ridiculing abolitionists and accusing them of lying about Missourians crossing into Kansas to vote illegally. Chestnut was deeply offended by the editorial, writing that he had seen the Missourians with his own eyes, "and so have hundreds of the settlers," and that the Missourians "made no secret of the object of their mission." Chestnut went on to say that when the Democrat editor "sneeringly talks of the outrages that have been committed, and insinuates that our case should excite no sympathy, he forfeits the respect and esteem of every respectable citizen in the land of steady habits."

Chestnut shared two sections of the Kansas Act to Punish Offenses Against Slave Property which banned the publication of anything that could undermine slavery and asked, "How would such laws suit your latitude? Wonder if the editor of the Waterbury Democrat would support them and call upon the editor of the N. Y. Day Book for Sharp's rifles to enforce them?"

Chestnut ended his letter on a positive note,

mentioning that the "Emigrant Aid Company of Boston are going to erect a

first class hotel" at Lawrence, Kansas. That hotel was the Free State Hotel, which pro-slavery men falsely accused of being a military fort, "designed as a stronghold of resistance to law... encouraging rebellion and sedition." The hotel would soon become targeted for destruction by the Kansas pro-slavery forces. (Sara T. L. Robinson, Kansas, Its Interior and Exterior Life, Boston: Crosby, Nichols & Co., 1856, p. 244)

In February, 1856, a prosperous cabinetmaker in New Haven announced plans to form a "Kansas Company" to emigrate to Kansas. Charles B. Lines was described by the Waterbury American as "an old an highly respected citizen" whose decision to move to Kansas was astonishing. Lines was forty-nine years old and had a large family as well as an established business. He sought to recruit men "of all professions, and especially farmers" who could "aid in establishing the institutions of New England, and to secure for themselves and their families a good home in that delightful country." Lines and his associate, Rev. H. A. Wilcox of Kansas, gave presentations in towns throughout Connecticut about their plan. ("Kansas Company from New Haven," Waterbury American, 22 February 1856, p. 2)

%20p2.png) |

| Advertisement in The Constitution (Middletown, CT), 5 March 1856, p. 2 |

By March, there were forty-two men in the company, seventeen wives, and thirty-nine children. The majority of the men were farmers, with two teachers, one physician, and several skilled craftsmen. Participants came from New Haven, Hartford, Middletown, Derby, Cheshire, Hamden, Meriden, Wethersfield, Guilford, Berlin, Bloomfield, New Britain, Plymouth, and New Hartford. Among them was Ira T. Neale, who had lived in Waterbury during the 1830s. ("Kansas Aid in New Haven," The New York Herald, 9 March 1856, p. 8 and William Almont Osmer, The Connecticut Kansas Colony of 1856-1857, Kansas State College Master's Thesis, 1953)

The Connecticut company's plan to settle in Kansas drew the attention of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe and an outspoken opponent of slavery who helped raise money for the Kansas Emigrant Aide Society. Beecher grew up in Litchfield, CT and was at this time pastor of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, NY. Beecher regularly lectured throughout the northeast and, in the winter of 1855-56, began advocating for equipping the Free State settlers with Sharps rifles.

|

| Henry Ward Beecher in 1858 Painting by Francis Bicknell Carpenter Collection of Nasher Museum at Duke University |

At his church in February, 1856, Beecher gave a speech in which he said that he "believed in the Sharp rifle--there was a greater moral power in one of those instruments far as the slaveholders of Kansas were concerned, than in a hundred Bibles.--You might just as well... read the Bible to the buffaloes as to those fellows who follow Atchison and Stringfellow; but they have a supreme respect for the logic that is embodied in Sharp's rifles. The Bible is addressed to the conscience, but when you address it to them it has no effect--there is no conscience there. Though he was a peace man, he had the greatest regard for Sharp's rifles, and for those who induced the New England men to use them." ("A Gunpowder Parson," The Weekly Telegraph (Macon, GA), 19 February 1856, p. 3)

Beecher secured an invitation to speak at New Haven's North Congregational Church on March 27, 1856, where Charles Lines was a deacon. The event was a fundraiser for the Kansas Company, with a goal of raising enough money to purchase twenty-five Sharps rifles for the settlers. Beecher was assisted at the event by Benjamin Silliman, a science professor at Yale. A number of Yale students were in the audience. The fundraiser was a success, but it also generated scandal. For many people, a churchman who appeared to be advocating violence and calling rifles "better than Bibles" was horrifying. The rifles were dubbed "Beecher's Bibles" by the pro-slavery newspapers, a name that quickly caught on in pro-slavery circles.

Supporters of the pro-slavery government in Kansas declared that any Free State settler who brought a rifle with him to Kansas was clearly the aggressor, that they could not claim to be acting in self-defense if they brought a weapon with which to defend themselves. The attendees at the church meeting were called "fanatics and mischief makers." The Free State men in Kansas were "notorious scoundrels" as well as "paupers, thieves, rowdies and lazy vagabonds that are swarming into Kansas from the North," while the group heading there from New Haven were "killers" armed with rifles given to them by Beecher. (Dwight, "Sharp's rifles better than Bibles!," Columbian Register, 29 March 1856, p. 2; "Sharp's Rifles in New Haven," Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1856, p. 2; "The Crazy Brains and Knaves of Connecticut," The Weekly Day Book (NYC), 29 march 1856, p. 4)

The

settlers set out from New Haven on March 31, 1856 with tremendous

fanfare. Hundreds of New Haven residents gathered to cheer them on their

way, with a parade escorting them to the steamboat that would take them

to the first stop on their journey. ("Departure of the Connecticut Colony for Kansas," New-York Semi-Weekly Tribune, 4 April 1856, p. 1)

|

| Benjamin Silliman in 1857 Painting by Daniel Huntington Collection of Yale University Art Gallery |

Charles Lines issued a letter to Beecher thanking him for his assistance and praising Beecher's gift of Bibles as well as rifles. While their religion would be the foundation of their work in Kansas, with their Bibles indicating "the peaceful nature of our mission, and the harmless character of our company" Lines valued the rifles for the ability "to teach those who may be disposed to molest us... that while we determine to do only that which is right, we will not submit tamely to that which is wrong." ("The Kansas Colony to Mr. Beecher," New-York Semi-Weekly Tribune, 4 April 1856, p. 1)

The New Haven colony eventually settled at Wabaunsee, Kansas after spending several months in Lawrence. By the end of April, they had been dubbed the "Beecher Bible Company" and were accused of using their rifles for an attempted assassination.

Ira Neale, one of the New Haven Company, returned from Kansas in October, 1856, paying a visit to his friends in Waterbury. Neale confirmed for them accounts of aggression by "the border desperadoes" under Atchison's lead, stating that "it is the settled purpose of the pro-slavery officials to keep out and drive off every emigrant whom they suspect" of being opposed to slavery.

Neale echoed William Chestnut's letter from the spring, saying that Free State settlers had put up with "the outrages upon their property and lives without resistance until patience ceased to be a virtue." ("Kansas," Waterbury American, 31 October 1856, p. 2)

Civil Disobedience in Osawatomie

In the spring of 1856, a group of Osawatomie men took a stand against the "Border Ruffian Legislature." On April 16, the group met and adopted resolutions opposing the payment of taxes to the illegally elected government. The group included William Chestnut, John Brown, and John Brown, Jr. The resolutions called the legislators "pretended and tyrannical" and "unlawfully assembled" with "no legal power to act." They pledged to support one another in "a forcible resistance to any attempt to compel us into obedience" and warned that anyone sent to assess or collect taxes from them "will do so at the peril of such consequences as shall be necessary to prevent the same." Rousing speeches were given by John Brown and others. (Letter from John Brown, Jr., "Original Correspondence," The Kansas Herald of Freedom, 10 May 1856, 3 and "Meeting at Osawatomie," The Kansas Herald of Freedom, 17 May 1856, p. 1)

|

| John Brown, Jr. Boyd B. Stutler Collection, West Virginia State Archives |

John Brown, Jr. was the leader of a volunteer military company called the Pottawatomie Rifles. When the Second Judicial District Judge, Sterling G. Cato, convened the new government's first court meeting at Dutch Henry's house on April 21, 1856, the Pottawatomie Rifles decide to attend as a group. One member of the company submitted a formal, written question asking if the court was enforcing the laws of the "Territorial Legislature, so-called." Judge Cato refused to respond, so Brown and his men left the court. Later that day, three members of the Pottawatomie Rifles submitted a copy of the Osawatomie resolutions to the judge, making their refusal to pay taxes official. Cato made no acknowledgment of the resolutions, but the next morning, he abruptly adjourned the court proceedings until September and left town. (Letter from John Brown, Jr., "Original Correspondence," The Kansas Herald of Freedom, 10 May 1856, 3 and "Meeting at Osawatomie," The Kansas Herald of Freedom, 17 May 1856, p. 1)

The Free State men were worried by rumors that mass arrests were about to take place. Judge Cato's arrival seemed to confirm those rumors, which led them to submit their written question. The Pottawatomie Rifle Company made a point of leaving their weapons at a log cabin not far from Dutch Henry's before making their appearance in Cato's court room, but this effort to appear peaceful went unnoticed by the judge. (Sanborn, The Life and Letters of John Brown, p. 229)

Cato was firmly on the side of the pro-slavery Missourians, describing the Border Ruffians as "peaceable, orderly and law-abiding." ("Our New York Correspondence," The Alton Weekly Courier, 17 April 1856, p. 1)

Cato's version of what happened during the Court session at Dutch Henry's was very different from Brown's (and other witnesses). According to Cato, he was "threatened by an armed force of fifty men, in full uniform" who tried to stop him from enforcing the laws. "..a notorious scoundrel... presented himself and interrupted the Court with written interrogatories. The Judge immediately ordered him out for contempt of Court. He was absent about one hour, when he again entered in full uniform at the head of fifty others, armed with Sharpe's rifles. He emphatically told the Judge, if he attempted to enforce the laws, they would resist 'unto death.'" ("Armed Men Threaten the Judge," The Kansas Weekly Herald, 24 May 1856, p. 1)

Newspapers all over the country reported only one sentence about the incident: "At Osawattomie, Judge Cato, of the District Court, had been prevented from holding a Court by threats of violence from Free State men." (Boston Evening Transcript, 28 May 1856, p. 2, and numerous others)

In May, 1856, a Grand Jury was convened and issued an indictment of John Brown, Sr., John Brown, Jr., William Chestnut, and seven other men who signed the April 16 resolutions. They were charged with having "unlawfully and wickedly" conspired to defy the laws of Kansas by refusing to pay taxes and were called "persons of evil minds and dispositions." The next court hearing was scheduled for July 14, 1856. By that time, however, a number of events had unfolded making it impossible to proceed. (Kansas Territory, U.S. District Court vs. John Brown and others for conspiracy, 1856-1858, Collection of Kansas Historical Society)

|

| U.S.

Marshal Elias S. Dennis commanded by Judge Cato to bring William

Chestnut before the Second Judicial District Court on March 8, 1858 to

answer to the charge of conspiracy. Kansas Historical Society |

During the same May session at which the Grand Jury issued indictments for the April 16 resolutions, Judge Cato issued a separate subpoena for John Brown, Jr., charging his with grand larceny for the theft of a horse belonging to George R. Hopper on May 23, 1856. William Chestnut was summoned to appear as a witness for the first court hearing on June 14, 1856. Again, due to other events, the court hearing was not held. (Kansas Territory, U.S. District Court vs. John Brown, Jr. for horse stealing, 1856-1857, Collection of Kansas Historical Society)

|

| Kansas Territory, U.S. District Court vs. John Brown, Jr. Kansas Historical Society |

The Sacking of Lawrence, Kansas

On April 23, pro-slavery Sheriff Samuel Jones was shot in the back at Lawrence by an unknown gunman (the New Haven emigrants, now called the Beecher Bible party, were suspected of doing the shooting with one of their rifles). Jones was relatively unharmed, although a bullet had to be removed from his back and rumors circulated that he had been killed or paralyzed. He quickly mobilized military support and began making numerous arrests of Free State men, some of whom had recently refused to join his posse. Free State Kansans anticipated not only arrests, but deaths, would follow under the pro-slavery concept of "law and order." Without aid from Congress, Free Staters were left to defend themselves against the pro-slavery forces gathering near Lawrence. ("Who Are the Ruffians Now?," Cleveland Weekly Plain Dealer, 30 April 1856, p. 3; "United States Troops in Lawrence," The Weekly Herald (NY), 3 May 1856, p. 7)

The news of these events was reported back to Waterbury by Charles Henry Barlow, a Waterbury schoolteacher who grew up in Meriden. After a year or two of teaching, Barlow decided to try his luck in Kansas. Like William Chestnut, Barlow regularly sent letters about his time in Kansas to the Waterbury American.

After Sheriff Jones was shot, Barlow sent a brief letter to the American with the details as he heard them (not all of Barlow's details were accurate, as he was in Topeka, not in Lawrence where the shooting occurred):

Yesterday six of the U.S. troops came to Lawrence with Sheriff Jones of Douglass county.... Last evening they camped out, and while Jones was outside of the camp some one fired a pistol at him but did not hit him. He then went into the tent and discovered that the ball passed through his pantaloons, but did not wound him.--The Marshal advised him to remain in the ten the rest of the night. About half-past ten some one came and opened the tent and fired at Jones; the ball passed into his spine. They endeavoured to remove it, but took away part of the spine in the attempt. Doubtless many will blame the Free State men for the act; but they must reflect that it is the same course which was pursued towards the Free State men last fall. Poor Dow was cut up with hatchets, and is it to be wondered at that some should so far forget themselves as to go farther than justice would demand. ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 9 May 1856, p. 2)

|

| Barlow's Letter from Topeka in the Waterbury American |

On May 10, Charles Robinson, who had been elected as Governor at Topeka by the Free State Convention (but was not recognized as the legal Governor by the U.S.), was arrested in Missouri for treason and remained in prison for four months.

A Grand Jury in Kansas issued an indictment against two newspapers, The Herald of Freedom and The Kansas Free State, as well as the new Free State Hotel, and recommended "that steps be taken whereby this nuisance may be removed." (Sanborn, The Life and Letters of John Brown, p. 235)

On May 20, former Senator David Atchison spoke before some five hundred Border Ruffians near Lawrence, cheering them for having "taught the damned Abolitionists a Southern lesson." He then instructed them to follow Sheriff Jones into Lawrence to "test the strength" of the new Free State hotel "and teach the Emigrant Aid Company that Kansas shall be ours." As for any Free State woman who dared to defend herself against the mob, Atchison said "when a woman takes upon herself the garb of a soldier by carrying a Sharpe's rifle, then she is no longer worthy of respect. Trample her under your feet as you would a snake! ...If one man or woman dare stand before you, blow them to hell with a chunk of cold lead." (Sanborn, The Life and Letters of John Brown, p. 234-235)

On May 21, 1856, about seven hundred pro-slavery men, led by Sheriff Samuel Jones, invaded the town of Lawrence, Kansas, whose population was mostly Free Staters. Jones' troops carried the U.S. flag and a flag which had a red background and a white star in the center, with the words "Southern Rights" inscribed. They attacked the two Free State newspaper offices, destroying the newspapers' presses and throwing the type into the river. They fired cannonballs at the Free State Hotel, then burned down what remained. They looted and vandalized numerous business and burned down Charles Robinson's home. ("Sack of Lawrence," Kansapedia Website; C. Henry Barlow, "Important from Kansas," Waterbury American, 6 June 1856, p. 2)

|

| Ruins of the Free State Hotel Illustrated in Sara Robinson's Kansas, Its Interior and Exterior Life, 1857 |

Henry Barlow was in Lawrence for these events and send a report to the Waterbury American on May 25 (published in the paper on June 6):

When I wrote to you last I promised to keep you advised of what transpired in this Territory; but there have been two things that prevented me--lack of time for one, and my being a prisoner when the most important events transpired. Col. Buford raised a company of one thousand men, armed to the teeth, to come out here and make this a slave territory. Soon after their arrival, the U.S. Marshal summoned them in his posse to make certain arrests that the pseudo Sheriff, Jones, could not make, and empowered them as a U.S. Company. Walking in the street one day, I was calmly informed that I was their prisoner--they forthwith took me up to the camp, examined me, asked me if I would vote to have this a free or slave State--told them at once, free--whereupon they told me they should be under the necessity of detaining me, and put me into a camp with Dr. Root of New Hartford, Mr. Mitchell of Middletown, Conn., and five others, where we were kept upon bacon, flour mixed with water and baked, which was our only living for over a week. On the 21st, these law and order loving citizens came to make the arrests, and met with no resistance. The arrests being made, the Marshal dismissed his posse, who all had on belts with "U.S." on them, which probably meant United Scoundrels. They then proceeded to make an attack on the Free State Hotel, (which was declared to be a nuisance by the Grand Jury, but never tried by any court. The hotel was kept by the Eldridges, one of whom was formerly of your city,) by placing the cannon within fifteen feet of the building. The first shot never hit it; but they fired thirty-two guns, (an enormous number) which made no impression upon it. They then fired and consumed it [set fire to it]; they also threw both of the free presses into the river and burnt Gov. Robinson's house--who is now under arrest for alleged high treason. After they had done all this they entered the houses and stores, destroyed the goods and clothing that they could not use, and even went so far as to take the boots from one man passing in the street. It was the grossest piece of vandalism ever witnessed in a civilized country.

Barlow begged for northerners to send help. He wrote that in Kansas "ladies sleep with revolvers under their pillows, and can used them, too, and will do it if occasion requires."

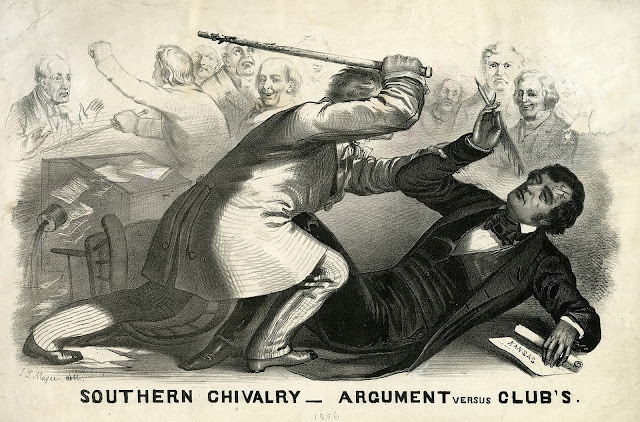

Two days before the sack of Lawrence, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts delivered a speech about Kansas in which he attacked Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina for perpetrating crimes against Kansas. On May 22, Butler's cousin, Representative Preston Brooks, brutally attacked Sumner at his Senate desk, beating him with a cane until the cane finally broke. Sumner lost consciousness long before the cane broke. He survived the attack, but never fully recovered.

|

| "Southern Chivalry" -- Brooks' assault on Sumner, illustrated by John L. Magee |

While

Northern newspapers were shocked and outraged by the vicious assault,

Southern newspapers took it in stride, calling the assault a

"chastisement" and expecting that Brooks' constituents would "justify

him for his timely punishment of one of the most accomplished

Freesoilers... that has ever disgraced the Senate Chamber." A Southern

letter writer went so far as to say that "South Carolina may well feel

proud of her son... he has shown his willingness to avenge her insulted

honor, no matter where the insult is offered or by whom." The writer

call the assault "chivalrous and self-sacrificing." ("Col. Brooks and Senator Sumner," The Abbeville Banner, 29 May 1856, p. 2; A.S.W., "Messrs. Editors," Yorkville Enquirer, 29 May 1856, p. 2-3)

Pottawatomie Massacre

On the night of May 24-25, 1856, in response to the news of what the pro-slavery forces did to Lawrence and what Preston Brooks did to Charles Sumner, John Brown led eight men (most of whom were his family) on a raid against pro-slavery men along the Pottawatomie Creek near Osawatomie.

Their first stop was the home of James Doyle and his

sons, who had prevented Free State Kansans from voting in 1855. Brown's

men took Doyle and two of his sons outside, then hacked them to death

with swords. Brown shot Doyle in the head to make sure he was dead.

The next stop was the home of Allen Wilkinson, a pro-slavery postmaster whom William Chestnut suspected of tampering with the mail of Free Staters. Wilkinson was also a member of the pro-slavery Kansas legislature and judicial branch. As with the Doyles, Brown's men took him outside and hacked him to death.

The final murder was that of William Sherman, brother of Dutch Henry whose house was used by the pro-slavery government for elections and court hearings.

Brown and his men

went into hiding after committing the murders. At least some of Brown's

sons were deeply disturbed by what they had done.

William Chestnut, who was not involved in the murders, was not upset about them. If anything, he was pleased and relieved. He wrote about the incident in a letter to the Waterbury American published on June 27, 1856:

We are in the midst of great excitements here just now and the slave interest is in danger of annihilation. For some time past the Missourians have been murdering and annoying the Free State men, but they now begin to find out it is a game two can play at. They have at last come to a realizing fact that slavery can never be introduced here, and are leaving the territory with their goods and chattels, giving it up as a bad job.

Five pro-slavery men have been murdered on the Pottawatomie Creek, about eight miles from here, and seven Free State men arrested on suspicion. I was summoned as a witness and attended court three days. I knew no more about the case than the man in the moon. The Judges were Missourians, and if not under the influence of "spirits of just men made perfect," they certainly had made the acquaintance of some of a different character. The court was held in a slab house or shed, and the way they meted out justice was a caution to Coke and Blackstone [English judges known for lying about the laws they enforced]. The murdered men had for a year past been threatening the lives of the Free State men in their neighborhood, and it was generally believed that they would ere long have carried their threats into execution, had they not been so summarily disposed of. As it is, one of the Free State men murdered at Lawrence was worth all five of them.

Testimony given by John T. Grant after the murders support Chestnut's claim that the murdered men were a threat to the community. Both William and Henry Sherman "were men of intemperate habits & when under the influence of liquor boisterous & quarrelsome, particularly William. Last summer, William's drinking & viciousness greatly increased. During the Spring past, he was engaged in several fights while under the influence of liquor." As for Allen Wilkinson, Grant stated that he was "a man of a bad disposition & evil temper" who was quick to draw out a knife "in a trifling quarrel" during a settlers' meeting at Dutch Henry's house.

William Grant, John's son, testified that William Sherman had recently shown up drunk at their house, "with a bottle in his pocket & a bowie knife in his belt & threatened that he would cut out the damned black hearts of my father, my oldest brother & sister." (Affidavits Concerning William and Henry Sherman, and Allen Wilkinson, 12 June 1856, Kansas Historical Society, Samuel & Florence Adair Coll. #161, Box 5, Folder 7)

William Grant testified again in 1879, describing an incident in which all five of the murdered men had taken a rope and threatened to hang a man for selling lead to Free State men, then returning to the man's house a few hours later to threaten him with an axe while his young children begged for his life. (Sanborn, The Life and Letters of John Brown, p. 255-256)

While the nation at large did not understand John Brown's decision to kill Wilkinson, Sherman, and the Doyles, the Free State people who lived there understood and appreciated his actions. Their pro-slavery government officials would do nothing to protect them, but John Brown did.

Battle of Black Jack

The Battle of Black Jack is considered by some to be the first battle of the Civil War, even though it took place five years before the war began. On June 2, 1856, John Brown's men attacked the encampment of Henry C. Pate, a pro-slavery Border Ruffian and Deputy U.S. Marshal. Pate was hunting for "Old Brown" seeking to arrest or kill him for the Pottawatomie murders. He had already taken two of Brown's sons, John, Jr. and Jason, as his prisoners.

After a three-hour battle, Brown and his men took Pate and twenty-two of his men captive. Brown and Pate negotiated an exchange of all prisoners: Pate and his men for Brown's two sons. Brown was assisted by Captain Shore, who later claimed to be the hero of the fight, a claim the Brown family disputed. (Sanborn, The Life and Letters of John Brown, p. 320)

John Brown had hard feelings for the people of Osawatomie at this point, believing that his son John had been betrayed by them, and called them cowards. (Sanborn, The Life and Letters of John Brown, p. 237-238)

William Chestnut sent an account of the battle, and the days leading up to it, to the Waterbury American. His letter was written on July 12, and published in the American

on July 25. It provides a perspective on events that differs from

accepted histories, drastically minimizing John Brown's role in the

battle, as Chestnut relied on information from Capt. Shore's men.

With regard to the accounts given of the only fair field fight between Free State men and the rum and ruffian Democracy, (the battle of "Black Jack," we call it, from the name of the creek,) I have seen no correct one. I was in the Free State camp for several days. We then mustered about 150 Free State men. General Toplift and Captain Brown came in from Lawrence and reported that the leading Free State men considered that the ruffians would rest satisfied with the destruction of Lawrence, for the present; that we would have no chance for an engagement; that we had better go home and get our planting done, and if any opportunity should occur to distinguish ourselves, by extinguishing a few ruffians, they would let us know it. The Osawatomie, Pottawatomie and Middle Creek men formed in marching order, and had got about one mile from Palmyra when we discovered a company of United States troops coming down the Santa Fe road. We held a council and concluded to march on to a high mound close by and encamp; we had just reached there when we received a dispatch from the Commander of the troops, requesting our Captain to wait upon him where he had ordered his men to halt, some mile and a half distant. Our Captain replied that he would not go, but if the Commander of the troops saw fit, he would meet him mid-way between the camps. They agreed to meet in this way, when, after an hour's conference, we were requested to disperse. We agreed to do so, and came on home. We had been home a few days when we learned that Captain Pate's company of ruffians were taken prisoners by Capt. Shore's company. Capt. Pate had thirty men, Capt. Shore only fifteen. They fought three hours on Black Jack Creek. The nature of the ground was such that both parties had considerable protection. Two of the Free State men were wounded in the beginning of the action, and the ammunition getting low, had to send two men off for a supply, leaving only eleven men -- Capt. Pate sent in a flag of truce, stating that his men surrendered; that he had eight men wounded and three had run away; the notorious Coleman was one of them. The noble little band took 27 prisoners. Captain Pate refused to give up his bowie knife--a very nice one, with a pearl handle--but a revolver held within a few inches of his nose made him unbuckle it and hand it over. All their horses, arms, ammunition, provisions, &c. were given up, but the United States troops coming up, the Free State men were ordered by them to deliver up the spoils and the prisoners too, and they did so. They managed, however, to secrete Capt. Pate's knife, his powder flask, and spur, and some six good revolvers. The boys take a good deal of pride in showing round these trophies of victory.--The above particulars I had from two men who were present and may be relied upon.

Chestnut placed heavy emphasis on Border Ruffian drinking habits, calling them "rum and ruffian Democrats, and speculating that "one reason why our affairs are so misrepresented, is that the ruffians being drunk most all the time, do not know what they are writing when when they undertake to report."

Barlow's Encounter with Ruffians

On

June 5, 1856, Henry Barlow made a trip to Kansas City to pick up a load

of freight (household goods) for an emigrant he employed. His return

trip nearly ended in his death by lynching, but he survived and wrote a very

colorful account of what happened which was republished in the Waterbury

American on June 20, 1856 (it was originally printed in The Chicago Tribune):

On my return with the load I was obliged to pass through Westport. When about a mile or a mile and a half from that village I came upon a camp occupied by sixty or seventy Missourians and Alabamians. Here I was met by a squad of these men, armed with muskets, rifles and side arms, who demanded of me to stop.

"Here's a d---d Abolitionist," was the cry; let us have him anyhow."

I produced a pass which had been given me by United States Marshal Donaldson; but they swore it was a forgery. They proceeded to break open the boxes in the wagon and to scatter the goods about in the road. While this was going on I was sent into their camp, where I was questioned thus:

"What's your name?"

"C. H. Barlow."

"Where do you live?"

"In Lawrence."

"Where are you from?"

"Waterbury, Connecticut."

"What are your politics?"

"I am a Free State man."

"How much money did that d---d Emigrant Aid Society give you to come out here?"

"None: I came out with my own money."

"Who gave you a rifle--Beecher or Silliman?"

"Neither: I brought no gun of any kind to the Territory."

"What the h--ll did you come our here for?"

"Why, to get a home and make money."

"And to make Kansas a Free State?"

"That's my intention, now I am here."

"Why didn't you go to Nebraska? That's a good country, and you d---d Yankees may have it; but Kansas you will have to fight for, and we'll whip h--ll out of you, but we'll get it, Union or no Union."

"That's a game that won't win, I'm thinking."

After much more of this sort, interlarded with impious oaths and ruffianly threats, I was asked:

"If we'll let you go, will you take a gun and march with the Pro-Slavery party?"

To this I had but one word in reply, and that was "NEVER."

Immediately there was a cry for "The ropes, boys! the ropes!" These were speedily brought and a noose was thrown over my head and around my neck, and I was dragged to the nearest tree.

I exclaimed, "You do not intend to kill me in this manner, do you?"

"Yes, G--d d--n your Abolition heart, and all like you."

I begged, if I was to be sacrificed to their fury and causeless hate, that I might have time to collect my thoughts and arrange my worldly affairs. I was told that if I had any property to dispose of, or my peace to make with God, that I would be allowed just ten minutes for both.

I gave a man among them, who, I learned, was called Bledsoe, and who seemed to think that I was to be killed without a cause, a schedule of my effects, and asked him to send it to my brother-in-law at the East, whom I named.

At the expiration of the little time given me, I was again dragged to the tree, the rope was thrown over a swinging limb, and, in spite of the remonstrances of Bledsoe and of Treadwell, who also began to plead my cause, I was jerked from the ground and suspended by the neck; I cannot tell how long, but probably for a brief period only, when Treadwell, who was called Major, and appeared to have command, peremptorily ordered me to be let down.

I was again questioned:

"Will you leave the Territory if we'll spare your life."

To this I demurred, saying that I had offended no law, or infringed no man's right.

The leader again interposed and told me that unless I would promise, he could not save my life. He told his men that I was guilty of no crime, except that of being a Free-State man; that I had a right to be, though he would admit that I had no right to such opinions in Kansas.

At last, his ruffian followers extorted from me the promise they required, giving me just twelve hours to make the promise good.

I was then sent with a guard to Kansas City, to see that I did not escape. My oxen and wagon were taken possession of, and I, with less than five dollars in my pockets, was forced to take the next boat and leave the country.

... My case is not a solitary one. Every man of my opinions who falls into the same hands is liable to the same abuse; and this, in Kansas, is called "Law and Order."

Barlow's account was disputed in pro-slavery newspapers, even as it was reprinted in newspapers throughout the country. The pro-slavery supporters found it impossible to believe that something like this could happen, accusing him of making it up, even though former Senator Atchison had repeatedly urged his followers to lynch abolitionists.

The New Haven Register ridiculed the "Kansas Outrage Manufacturing Company," dismissing all accounts of atrocities committed by the Border Ruffians, while trying to undermine Barlow's account of what happened to him. (Hartford Courant, 18 June 1856, p. 2)

Barlow's reputation was upheld by many who knew him. Thomas Church Brownell, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church and Treasurer of the Connecticut State Teachers' Association, wrote, "For several years past, Mr. Barlow has been a member of our State Teachers' Association, and has received the esteem and confidence due only to an upright and worthy man. His character entitles his statement to entire credence, and if he is not safe from 'the ropes' of border ruffians, I know of no Connecticut man who would be--unless he would take a gun and march with the pro-slavery party." ("Barlow Reliable," Hartford Courant, 18 June 1856, p. 2)

The Waterbury American declared that Barlow's honesty had never been questioned, and he had "an unblemished reputation" in Waterbury. The paper reached out to someone from Meriden who was able to vouch for Barlow's "respectability and veracity" in that town as well. ("C. H. Barlow's Statement," Waterbury American, 20 June 1856, p. 2)

Charles Lines followed up with a letter describing his experiences, confirming Barlow's statement. Lines wrote that "it is not safe to go over the usually traveled road to Kansas City." He and a number of other men who had to travel "camped last night on the road that has been a good deal infested with these border ruffian guerilla parties... the Slave party are constantly harassing, robbing and killing the innocent." ("Kansas Matters," Waterbury American, 27 June 1856, p. 2)

Barlow returned to Waterbury at the end of June, 1856. He was invited to give "a brief narrative of his experience" in Kansas at Hotchkiss Hall on June 28. The audience was "highly respectable and attentive" to his "unvarnished" retelling of the many incidents he had witnessed and experienced in Kansas. ("A Talk from Kansas," Waterbury American, 27 June 1856, p. 2; "Mr. Barlow's Statement," Waterbury American, 4 July 1856, p. 2)

Rev. S. W. Magill, pastor of the Second Congregational Church, which Barlow had attended while he lived in Waterbury, also spoke that night at Hotchkiss Hall. Magill was an abolitionist who had grown up in the South. He made "some interesting remarks... which should at least teach a lesson of charity to some of [Barlow's] defamers."

Waterbury's other newspaper, the pro-slavery Democrat, ran an editorial written under the pen name "Julius Seize-'er" attacking Barlow's credibility on the grounds that Barlow owed money that he was unable to pay. In Barlow's defense, "Justitia" submitted a letter to the American noting that "it is the misfortune of Mr. Barlow that he narrates an experience during his residence in Kansas not very credible to the men whom the present Administration has placed in power in that Territory; and not very palatable to the party who are determined to stand by that Administration, and to justify it in whatever it may have done." ("Distinguished Arrivals!," Waterbury American, 4 July 1856, p. 2)

The Democrat also ran a sarcastic notice of Barlow's program at Hotchkiss Hall, which the American later suggested might actually have helped increase attendance at the event:

Professor Barlow's thrilling narrative of his adventures with the "border ruffians,"--including a minute description of the manner in which he was roasted alive, fricaseed, and afterwards "chawed" up. A horrifying account of the "hanging" scene will also be recited. This alone will be of sufficient interest, it is to be hoped, to ensure a crowded house. A collection will be taken up for the benefit of all "interested" parties. (Waterbury American, 4 July 1856, p. 2)

Barlow gave a second program detailing his Kansas adventures while he was in Stamford, where he was persuaded to stay overnight so that he could give a last-minute performance. With only two hours' notice, an audience of nearly three hundred people assembled at the Congregational Church to hear him speak. Barlow was introduced by Rev. E B. Huntington, who had known him for many years, vouched for his honesty. Local Democrats were upset by the use of the church, saying it was a "desecration of the House of God to permit it to be used for such a purpose... that the church might with just as much propriety be used for a house of prostitution." Events in Kansas had become so politically charged that many refused to acknowledge the truth of what was happening there. ("The Lecture on Kansas," Stamford Advocate, 22 July 1856, p. 2)

The situation was complicated by the abundance of rumors. There were so many false stories circulating, it was easy for Democrats to dismiss all stories. William Chestnut wrote about some of them, from "an account of the hanging of a Free State man in Osawatomie by the Pro-Slavery party" to an account of "two Free State men in this vicinity who were attacked by eight Pro-Slavery men. The former killed five of the eight and neither of the two received a scratch!" ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 25 July 1856, p. 2)

While clearing up rumors, Chestnut emphasized that the danger was real, writing "the eastern people can never know the extent of the suffering of the Free State men in Kansas, unless they come here and see it. No man is sure of his life a minute, or of his property an hour."

Skirmish at Osawatomie

The town of Osawatomie was invaded on June 7, 1856. William Chestnut described it as follows in his letter to the Waterbury American:

...a company of Missourians, numbering about 150 men, came into Osawatomie, armed to the teeth. The male residents were mostly away in the fields or workshops, and there were not over twenty at home. The ruffians entered the houses, broke open trunks, chests, carpet bags, and ransacked everything they could find, carrying off every article of value they could lay their hands on.--They even stripped the girls' fingers of their gold rings and robbed them of their ear-rings. They stole sixteen horses and carried off all the arms and ammunition they could find. The principal buildings were set on fire several times, but we succeeded in saving them. They were in a great hurry to get off, or we should have fared a great deal worse. They tried hard to get our printing press, but we made out to conceal it. They even threatened to hang a girl, a domestic in the printer's family, if she did not tell where the press was hid. One poor fellow lost $400 in cash, and others smaller sums. They said, "we would all have to leave the Territory and they were going to sweep it of every d---d Abolitionist," and that they should "keep the field all summer, as it would pay a d---d sign better than planting corn." They looked like the refuse and scum of the whole South.

To-day [June 11] another company of U.S. troops came to our relief, and we think we can defend ourselves with their assistance; but we want men, arms and money from the North and East, or it will go hard for us. ... The war has fairly begun, and if we fail, it will be the fault of the North. The Free State men here will die, to a man, before they will suffer themselves to be deprived of the rights secured to themselves by the constitution of our common country. We have drawn the sword and thrown away the scabbard. We wish to secure this delightful country for freedom; and the time has gone by when freedom's sons will consent to be penned up in the chilly regions of the North.

Chestnut

expressed annoyance with the presence of federal troops supporting the

pro-slavery forces in Kansas and longed for an insurrection against

them, blaming them at least in part for the June 7 raid on Osawatomie.

If the troops were only out of our way, we could take care of ourselves; and we could very easily put them out of the way, if our leaders had not determined to avoid a collision with the General Government. At present the troops are doing all they can to disarm and disperse Free State men, and at the same time regulating their movements to suit the ruffians. We have damning proof of this in the sacking of our town.

Free State Kansas Bill in Congress

The state constitution adopted by the Topeka Free State Convention in October 1855 was debated by Congress in July 1856. A bill to admit Kansas into the Union as a Free State was initially rejected in the House of Representatives by one vote, then reconsidered and passed by three votes. Most observers expected the bill to fail in the Senate, as it did, but supporters still saw this as "a highly gratifying result" believed that it would "cheer the hears of the settlers in Kansas, by showing them that there is a popular sentiment uprising in their behalf." ("Passage of the Bill for the Admission of Kansas as a Free State," Albany Journal, 5 July 1856, p. 2)

The Free State Kansas settlers were far from cheered by the bill's failure. When the Free State legislature gathered at Topeka in early July, President Pierce ordered Col. Edwin Sumner's troops to disperse them as "an unlawful assemblage." Sumner arrived on July 4 and, with deep regret, saying "this is the most painful duty of my whole life," ordered them to disperse. (Thomas K. Tate, General Edwin Vose Sumner, USA: A Civil War Biography, McFarland & Co., Inc., 2013, p. 53)

|

| "Col. Sumner Arriving at Constitution Hall," from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, July 26, 1856 Retrieved from Library of Congress |

William Chestnut, who was not at Topeka, gave the following update on how the Free State men viewed the political situation in his July 12 letter to the Waterbury American:

Our men have just got back from Topeka; we could not send many men as we expected another attack on our town. We keep guard every night, and are determined to give the "law and order" party a public reception if we get a chance. The leading Free State men have concluded to wait the action of the present session of Congress, and if they will not give us redress we will at once appeal to all just citizens for the justness of our cause, take the field at once, and keep it until we make free homes or find graves in Kansas. It is the opinion of our leaders that we have at present fifteen Free State actual residents in the Territory for [every] one and ruffian Democrat. I think this is a very low estimate of our strength.

Competing Settlements

While frustrated by the successes of the pro-slavery groups, William Chestnut continued to promote Kansas as the best place to settle, writing that "for health, wealth, or pleasure, this Territory possesses great advantages over any other portion of the United States... Enterprising young men from the East have now an opportunity of making themselves independent in a few years. They can now get land cheap, and at once have all the advantages of an old State. The fearless and brave can obtain a rich reward for themselves and at the same time assist in saving this beautiful country from the curse of slavery." Chestnut signed his July 12 letter, "Yours, for Truth and Freedom."

Some of Chestnut's motivation for promoting Free State settlement came from the arrival of a "colony from Georgia which consists of ninety men, besides women and children" only three miles from Osawatomie, "well supplied with everything necessary for a settlement." He saw this as part of a movement to increase the territory's small pro-slavery population, "sending in families by the hundred."

Chestnut reported that the pro-slavery "men of influence" in Kansas "have stated publicly that their ruffianism must be put down; that it has almost ruined their cause, and nothing now can save Kansas for the peculiar institution but the utmost energy and activity in colonizing it with the faithful."

The "Georgian colony" near Osawatomie soon proved to be far more than a peaceful group of settlers looking for a better life. What happened next was a swift escalation of violence at Osawatomie.

On August 18, 1856, William Chestnut sent the following report to the Waterbury American, which published the report on August 29:

Fierce war with its concomitant horrors is upon us. The Georgian colony located here about two months since, is numbered with things that were. They came here under the pretense of making a settlement and to build a new city called New Georgia. They bro't along with them a wagon load of whiskey, and spent most of their time in stealing, drinking and gambling. but as the whiskey grew "beautifully less" by degrees, about two weeks since the whole cargo became entirely exhausted. Having in the interim constructed a kind of rough Fort as a place of rendezvous upon the site of their proposed city, to protect and store away their plunder, they stole into our town in small squads, as opportunity offered; stealing everything they could lay their hands on, getting drunk and disturbing the peace and quiet of our community. We bore with these repeated outrages until forbearance ceased to be a virtue. Accordingly, on the 9th instant, a company of Free State men from our place and vicinity, assembled and marched to the Georgia camp about one o'clock the next morning, expecting to find some sixty or seventy men within their Fort. The company came to a halt, and the order given to demand an unconditional surrender--when, judge of their surprise to find that the chivalry had fled, leaving behind their cattle, horses, &c., with about 1000 lbs. of flour, 2000 do. of bacon, some corn meal, sugar, ready-made clothing, and coffee, valued at about $300--a very timely prize to the Free State party.

Historians have disagreed on the details of what happened when the Free State troops attacked the New Georgia fort. While Chestnut says it happened on August 10, some histories say it was August 5 or August 7. Rumors and false information about the incident were published by both sides at the time, creating a confusion that persists to the present day.

Pro-slavery newspapers demonized John Brown and exaggerated the events of that day:

On the 7th inst. Brown, the notorious assassin and robber, with a party of about three hundred abolitionists, attacked and drove into Missouri, Cook and a colony of Georgians which had settled near Ossawattamie. This colony was unarmed, and numbered in all, men, women, children and slaves, about two hundred. Their houses were burned, all their property (even to the clothes of the children) taken or destroyed. ("Lane's Men Have Arrived--Civil War Is Begun," The New York Herald, 27 August 1856, p. 1)Free State newspapers reported that the houses at New Georgia were burned by the Georgians "for effect... to get up an excitement." The members of the Georgia Colony, however, insisted that their houses were burned by John Brown's men. They explained their nonexistent defense of their fort, and the apparent abandonment of the colony prior to the raid by saying "our women and children, together with our sick men, had been removed on account of threats having been made against us, and the remainder, with the exception of a guard of six men, were scattered in different places--some on their claims, and others attending to business for the colony when the attack was made." The Georgians claimed they were the victims in the conflict, since John Brown's men, "numbering some three hundred, were only about two and a half miles distant, and daily threatening our lives." ("To the Public," The New York Herald, 27 August 1856, p. 1)

The Battle of Osawatomie

Three weeks after New Georgia was invaded by the Free State military, Osawatomie was once again invaded by pro-slavery forces. The Battle of Osawatomie, on August 30, was significantly worse than the invasion that happened on June 7. It has been called the "culmination of numerous violent events in Bleeding Kansas in 1856" and helped cement John Brown's legendary reputation. ("Battle of Osawatomie," Kansapedia website)

Free State and pro-slavery troops engaged in skirmishes and raids in the days leading up to the battle. Pro-slavery leadership urgently wanted to capture John Brown; Captain Hiram Bledsoe convinced General Reid to burn down Osawatomie and destroy Brown.

On the morning of August 30, a pro-slavery Baptist minister, Martin White, guided Reid's troops into Osawatomie. Before reaching town, they encountered a party of Free State men led by John Brown's son Frederick. White shot and killed him on sight.

John Brown was notified of his son's death and of the approaching army. He rallied his troops for the defense of Osawatomie, but the battle ended when they ran out of ammunition. In a final effort to save the town, Brown had his troops flee in different directions, hoping to lure the pro-slavery men away from Osawatomie.

The only women in town at the time were William Chestnut's wife and

daughters, and the women of the Sears family. At one point in the

battle, Reid's army formed a line stretching from Chestnut's house to

the house of O. C. Brown (no relation to John Brown). (William G. Cutler, "A Contemporary History of the Battle of Osawatomie," 1883; Genuine Kansas website)

Reid's men instead plundered and burned nearly all of Osawatomie. The Adair's cabin was one of the few buildings to survive, as it was located outside of town.

|

| Postcard view of the Adair Cabin in the early 1900s Kansas Historical Society |

William Chestnut's account of the battle, written on September 27, was published in the Waterbury American on October 17, 1856:

On the morning of the 30th of August, we could not muster over 30 men, (several having gone East in despair,) when a report came that 600 Missourians with several pieces of artillery, were marching down directly for this place--several others left on hearing the report. Captain John Brown happened to be here, and declared that if the men would stick by him he would defend the town. In the course of the morning, Capt. Reed, of Independence, made his entry with about 400 men and one cannon. By dint of exertion we collected thirty men, but ten of them subsequently left, so that only about 20 remained. The enemy opened their cannon upon us, when the battle commenced in earnest, and we were finally driven across the stream, and were forced by superior numbers to retreat for safety. Our whole loss was two killed and three wounded. The enemy took two prisoners, in addition to two others whom they killed on the spot. They also killed two others, one of whom was called "Dutch Charlie,"--him they scalped and took his brains out. He had been in the battle of Black Jack, when Captain Pate was taken.--Captain Reed lost 34 killed and 45 wounded--rather a dear bought victory. The town contained about thirty buildings, one-half of which the enemy burnt, including the business part of the settlement. The steam mill fortunately escaped destruction. You can imagine the scene of terror which filled the minds of the women and children, burned out of house and home, with nothing but destruction around them, without clothes or provisions, or where to lay their heads.

After the battle, William Chestnut turned his attention to helping his neighbors recover from the near-total loss of everything they had.

Donations from Waterbury

William Chestnut sent a request for aid to Waterbury, asking if "my friends in Waterbury would raise a little fund for this place and send it to me," promising to "see that it is faithfully applied." Chestnut was worried that the people of Osawatomie would struggle to survive the winter after losing so much of what they had. He was also worried that some of the community's Free State men would give up on Kansas without assistance. ("Kansas--the Free State Sufferers," Waterbury American, 17 October 1856, p. 2)

The first donation came from Julia A. Pratt, who sent three dollars to the American to start up a Fund for the Relief of the Osawatomie Sufferers. ("Kansas Donation," Waterbury American, 24 October 1856, p. 2)

On Thanksgiving Day, a collection was taken up at the Second Congregational Church, raising one hundred dollars which was sent to the National Kansas Committee at Chicago ("Kansas Donation," Waterbury American, 12 December 1856, p. 2)

Chestnut learned from friends in Waterbury about donations being collected. He asked for the donations to be sent directly to Osawatomie, as it would "save both expense and considerable delay." He promised that any donations sent to himself, or to either Rev. Samuel Adair or Rev. Amos Finch, would be "honestly and faithfully" used. ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 19 December 1856, p. 2)

Claims for Damages

In 1857, the Kansas legislature established a process to review claims for damages during the previous two years, forwarding that information to Congress in the hopes that Kansans would be compensated for losses caused by the "difficulties" that had occurred. The Commissioner for Auditing Claims held sessions at sixteen locations in Kansas from September through December, 1857. Claimants were required to submit their claims in the form of a petition with all supporting documentation attached. More than a quarter million dollars worth of claims were approved by the Commissioner and submitted to Congress for approval and payment, but none of the claims were approved or paid. ("Notice to Claimants," The Kansas Herald of Freedom, 12 September 1857, p. 4; M. H. Hoeflich & William Skepnek, "Claims for Loss in Territorial Kansas," Kansas Law Review, Vol. 65, 2017)

In 1859, the Kansas legislature appointed a second commission to investigate all claims of losses. This time the commission consisted of three people instead of just one. Claimants were required to give sworn testimony and to present at least two witnesses to support their claim. William Chestnut served as a witness for several Osawatomie claims, giving his testimony in May, 1859. (Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives Made During the Second Session of the Sixth Congress, 1860-61)

For his testimony regarding the destruction of John Sharkey's general store, Chestnut gave a detailed account of what happened on both June 7 and August 30, 1856:

On the said 6th day of June, 1856, between two and four o’clock p.m., a body of armed men, on horseback, about 20 or 30 of whom I saw, entered the town of Osawatomie, as I understood, by the steam mill ford across the Marais des Cygnes, and committed robberies by force. They plundered several dwelling-houses and stores… and carried away money, goods, and property from those places collectively, and tried to fire some of the buildings. They seized and took off with them several horses belonging to residents of the town. At that time about 30 buildings comprised the town of Osawatomie, and the actual population was about 200 persons, including men, women, and children. About 40 or 50 of those inhabitants were men capable of bearing arms. Most of those men were then absent, at work on their claims outside of the town, or absent on business, so that, I heard it stated and estimated, shortly after the robbery, that there were only five or six men in the town when the hostile party entered and committed their depredations; no resistance was attempted.

I do not know of Mr. Sharkey sustaining any further loss until the 30th day of August, 1856, when the town of Osawatomie was invaded by General Reed and his army of 400 Missourians, aided by Rev. Martin White, and almost entirely destroyed, including Sharkey’s store and his entire stock of goods, such as above described. My dwelling-house was about half a mile southwest from Sharkey’s store. I was home on that day, and saw Reed’s forces enter the town. They were all mounted on horseback; they entered the town from the northwest, having come from the head of Bull creek and crossed at about sunrise. They did not come to my house, but passed within about a quarter of a mile from my house; I stood by my house, saw the invading force pass to the houses forming the town, and soon after heard firing about the houses and in the woods. The houses forming the town are located on a level prairie on the south and west side of the Marais des Cygnes, and east and north of Pottawatomie creek, which forms a junction with the Marais about three-quarters of a mile from the town settlement; most of the houses are within a quarter of a mile of the Marais and three-quarters of a mile from the Pottawatomie, and surrounded on three sides by timber. From where I was I could not see the citizens flee from their houses; there had not been any additional force posted in the town over night for its defence. Nothing was known of the approach of the hostile force until they made their appearance on the hill west of the town. The country was then in a state of civil war, and an attack on Osawatomie by the Missourians had been threatened for two or three weeks previous, in consequence of which many of the citizens of Osawatomie had fled with their families, and no business of any consequence had been done for several weeks. I saw the invading force bring with them a large cannon. On reaching the buildings the company principally dismounted, and I could see them about the houses. Shortly after I heard the cannon firing against the timber of the Marais des Cygnes, immediately north of the town, and firing of small arms in and out of the timber. This firing continued an hour or an hour and a half, after which they gathered about the houses, collected their horses, and set fire to most of the buildings of any consequence in the place. [gives list of 22 buildings destroyed]

The invading force retired from the town about 9 or 10 o’clock a.m., taking with them a number of wounded and dead. They took away with them as prisoners William Bainbridge Fuller, Robert Reynolds, Dutch Charley Kaiser, a young man named Thomas, from New York, a Mr. Morey, Spencer Brown, all belonging to the town; also a man named William Williams, belonging to Miami Village, Kansas Territory. They shot and killed said Williams, on the Osawatomie town site, before they left, and after they had taken him prisoner; Dutch Charley they shot and killed on Cedar creek on their return to Missouri. Before entering the town they killed Frederick Brown and William Garrison, and wounded George Cutter very badly. During the battle and flight of the citizens, the Missourians killed George Partridge, as he was crossing the river on horseback, and a young man named Powers, formerly from the neighborhood of Freeport, Illinois. There were engaged in the battle in behalf of the town, under command of Captain John Brown, commonly known as Old Brown, 17 men; under Captain Cline, 14 men; and a few citizens of the town, under Captain Updegraff, numbering about ten men; total 41 men. They retired to the woods, as above mentioned, and continued to return the fire of the enemy until driven from their position by the cannon mentioned.

As before, Congress did not approve or pay any of the claims.

Rebuilding Osawatomie

By December, 1856, William Chestnut could report that Osawatomie was on the mend, with "three good stores opened" and a grist mill being built in the basement of the saw mill. He described the troubles with border ruffians as a storm that had passed, "a tornado which has leveled our dwellings with the earth, destroyed our towns, and spread ruin and desolation far and wide. But though crushed to earth, we shall rise again." ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 19 December 1856, p. 2)

New arrivals from Iowa and other eastern states gave Chestnut hope that they could "build a barrier of freedom on our frontier that will laugh to scorn all the machinations of all the villainy of the border ruffians."

Chestnut looked forward to more land opening up with the sale of land held by local tribes. While he regularly spoke against slavery, he spared no thoughts of concern for what was happening to Native Americans in Kansas, taking for granted that their lands should belong to white men.

It is expected that the Miami reservation will be sold next Summer; it contains as good land as is to be found in the Union, and the sales will excite nearly as much interest as the present land sales of the Delawares' lands in the North. Our town is bounded on the South-east by the Miamies, and on the North-east by the Peori and the Piankashaw's lands. When these lands are sold, which will be soon, they will add immensely to the natural resources of this section. The Indians had a cunning eye when they selected these lands.

He reassured prospective white settlers that they had nothing to fear from the Indians: "they are no more troublesome than the Mohegans in Connecticut."

By the spring of 1857, Osawatomie boasted three blacksmiths who were starting up a plow factory. The saw and grist mill was in constant operation, and Chestnut boasted that they had "more timber and better water here than can be found in many places in the Territory." ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 10 April 1857, p. 1)

Chestnut was happy to report the death of "Dutch Henry" Sherman, who was murdered on March 15, 1857. Like his brother William Sherman, who was killed in the Pottawatomie Massacre, Dutch Henry was considered to be a threat to the Free State community.

You will probably have seen an account of the shooting of Dutch Henry, about seven miles from this place. He was a very troublesome character, and had been threatening the lives and property of Free State men for the last two years; his removal gives general satisfaction.

Life in Osawatomie remained relatively calm. William Chestnut was a delegate for his district at the March 1857 Free State Convention in Topeka, which was held without interruption. During the trip to Topeka, Chestnut "was pleased to observe the reviving influences of New England thrift and enterprise on the route." The previous year, that same route was filled with "desolation and ruin" with abandoned cabins.

In May, 1857, Chestnut reported that "houses are going up just as fast as the mill can turn out the timber" and that rents were skyrocketing with the increased demand as the population grew. Osawatomie had become a small boom town, ready to move on from the "troubles" of Bleeding Kansas. ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 12 June 1857, p. 1)

The Election of 1857

William Chestnut and his neighbors at Osawatomie were prepared for violence on Election Day in 1857. After the election, Chestnut was pleased to report that all 240 votes at Osawatomie were Free State: "Not one pro-slavery or National Democractic vote was offered throughout the whole day. Your readers must bear in mind that this is one of the doubtful counties." ("Correspondence of the American," Waterbury American, 16 October 1857, p. 2)

Chestnut credited the election results to "our military organization. We were well armed and drilled, and determined none but legal voters would be allowed to vote, let the consequences be what they might. We made no military display during the election, but we had our arms where we could get them on short notice, if we needed them. I have not heard of one Missourian trying to vote in this county."

Afterward

William Chestnut became Osawatomie's first historian, writing a "Sketch of the History of Osawatomie" in 1857. He continued to send letters to the Waterbury American for many years, promoting Kansas as an ideal state for farming.

Once slavery was abolished, Chestnut turned his attention to civil rights, advocating for expanding the right to vote to all adults, regardless of gender or race.

When an 1867 state referendum to remove the words "white" and "male" from the qualifications for electors failed, Chestnut was deeply disappointed. He wrote that the "hopes of the friends of freedom" now lay with the federal government adopting a law "defining the qualifications of citizenship throughout the Union... If we really believe that "All men are created free and equal," is it not time... we guaranteed this fact." ("Letter from Kansas," Waterbury Daily American, 19 November 1867, p. 2)

In the same letter, he remarked on the latest influx of immigrants to Kansas, writing that the roads "are crowded with caravans of trains of wagons, horses, cattle &c. from all parts of the Union. Some of them I fear will find a pioneer life more than their fancy has painted it, but the brave hearts who are willing and able to endure the privations of such a life, there is a glorious future."

No comments:

Post a Comment