At some point during the 1860s, Laura Russell met Zophar Pearsall, a prominent New York City butcher with a shop at Fulton Market and a home on Second Avenue. His customers included major hotels, steamship lines, and wealthy private homes. Zophar was nearly 30 years older than Laura and divorced. He was also very wealthy. Laura and Zophar married and had two children together.

Although Zophar continued his NYC business at Fulton Market, the family maintained a home in Waterbury, next door to Laura’s grandmother. Their house was large, with room for the family, three servants, and guests.

Zophar died in 1883 after a long illness. Laura and her son, also named Zophar, continued the Fulton Market business. All went well until 1890, when Laura was named as co-respondent in a divorce suit between Sarah and Edwin Camp. Sarah Camp claimed damages against Laura for the “alienation of Mr. Camp’s affections” and additionally claimed that Edwin gave Laura over $40,000 worth of property during their affair.

The newspapers of the era loved this sort of sordid story, and details of the case appeared in papers around the country. The Meriden Daily Republican described Laura Pearsall as “a plump and attractive brunette of 40” whose now-deceased husband had hosted gatherings of New York brokers and prominent Connecticut businessmen in their Waterbury home.

According to the divorce suit, Edwin Camp had been hired to help take care of Zophar during his final illness. After Zophar’s death, Edwin stayed on as Laura’s assistant, helping her run the Pearsall meat business at Fulton Market. Edwin and Laura insisted that their relationship was purely professional; Sarah claimed that Laura seduced Edwin. Sarah’s attorneys had at least one witness testify that he had seen Laura and Edwin kissing (and perhaps a bit more) at Laura’s home. The defense claimed that Edwin was in the habit of kissing every woman he knew, and that it was quite common to greet someone with a kiss in other countries. When pressured by additional witness testimony, Edwin claimed that he was taking care of Laura while she had pneumonia, and was merely applying medicinal lotions to her neck and chest.

Laura Pearsall did not cope well with the stress of the divorce trial. When a Waterbury constable attempted to serve her notice to appear in court, she had her dog attack him. A witness in the case and one of Laura’s neighbors, James Finnerty, accused her of attacking him with a horse whip. This was another story that the newspapers soaked up and embellished. The Harrisburg Daily Independent wrote, “Being a woman of large proportions and great strength, every blow told.” The Altoona Tribune claimed that Laura weighed 250 pounds. Laura’s attorney later insisted that her supposed victim had severely exaggerated the story.

|

| From the Raleigh State Chronicle, 26 June 1891 |

Laura Pearsall and Sarah Camp settled their dispute out of court, and things quieted down for a time. Laura and her son, Zophar Pearsall Jr., continued to operate the Fulton Market business. Laura’s daughter, Emma Louise, married William H. Hylan in 1888 and had a daughter, Laura Linola, born in 1891. The Hylans lived with Laura and young Zophar in Waterbury. The Pearsall home and land was often referred to as “Pearsallville” and included a large tract of waterfront property at the intersection of North Main Street, Lakewood Road, and Farmwood Road.

In 1896, Laura Pearsall announced that she would be opening up 17 acres of her land as a park, with the help of New York investors. At the time, Pearsall’s property was a mile from the end of the North Main Street trolley line, but the line was extended to Lakewood Road to accommodate her park, making it easy for city residents to take the trolley from Exchange Place downtown to the main entrance of Waterbury’s new summer resort.

Laura’s park was named Lakewood Park. Order was kept by a private police force of six, led by Waterbury deputy sheriff W. J. Rigney. Laura, who was horsewhipping her neighbor a decade earlier, declared the park to be a place “where ladies and children can visit without fear of molestation or insults.” The American Band performed during the afternoons and evenings. The facilities included a dance hall, bowling alley, and cafe. Vaudeville performers were added to the performance schedule.

The park was spread out on either side of Lakewood Road. The lake to the south of the road is Belleview Lake, and the Belleview Lake Grove Pavilion was built there for dancing and other entertainments. Boats could be taken out onto Belleview Lake.

|

| Lakewood Park, 1898. From the Bridgeport Herald, 22 May 1898 |

|

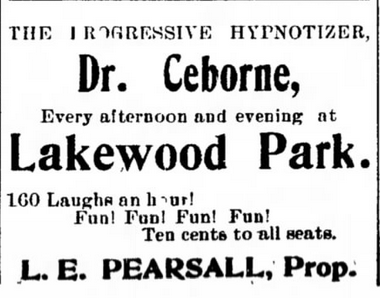

| Advertisement in the Naugatuck Daily News, 11 May 1899. |

|

| Advertisement in the Naugatuck Daily News, 12 July 1899. |

|

| Advertisement in the Naugatuck Daily News, 27 July 1899. |

In 1900, the Pearsalls decided to hand over the park operations to theater impresario Eugene “Jean” Jacques and William B. Richardson. Jacques and Richardson leased the property, changing the name to Forest Park. An estimated 5,000 people attended opening day (Sunday, June 17), with extra cars running on the trolley line from Exchange Place.

Jacques and Richardson made significant additions to the park. They built a rustic entrance gate, turned the dirt road leading into the park to a macadam road, added a fountain to the pond near the entrance, built pavilions with drinking fountains over two springs, raised the level of the lake by three feet and built a bandstand over the water, built an outdoor vaudeville theater, added a merry-go-round and arcade, and planned for a Ferris wheel. The entertainments included a refreshing walk through the woods, balloon ascensions, rowboats, a bowling alley, water shows, and even a small steamboat for excursions around the lake. Concessions included a bar, restaurant, ice cream, confectionery, peanuts and popcorn. During at least one summer, Madame Zingara, a gypsy fortune-teller, was a park feature.

|

| Belleview Lake Grove Pavilion, circa 1900. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

In 1905, Jacques and Richardson’s lease of the park expired. Laura and her son Zophar took over management, restoring the name Lakewood Park and adding new features. For a time, the park was subdivided into four businesses: Lakewood Park, managed by Zophar Pearsall; Forest Park, managed by McMorris; Forest Lake Park, managed by Jason A. Blake; and Belleview Lake Grove.

|

| Map showing park buildings and roads on either side of Lakewood Road, 1909. A.J. Patton Map of Waterbury, Town Clerk's Office. |

|

| Boating at the park, circa 1905. |

Zophar Jr. made frequent appearances in the newspapers, sharing stories that were apparently designed to draw attention to the park in unconventional ways. On December 2, 1906, the Bridgeport Herald ran a story about the ghost of “Batty” Malone terrifying Zophar Pearsall. Malone, an Irish immigrant, drowned in Belleview Lake during the 1860s. The story in the Herald (which should be taken with numerous grains of salt) alleged that Malone’s ghost had been seen for years by the Finnerty house before settling into a nearby log cabin.

Zophar Pearsall claimed that his first encounter with the ghost occurred while fishing from the bridge at night. Something tugged so hard on his line, he fell into the water. When he pulled himself out, he claimed to have heard a “taunting laugh.” The laugh followed him on his way to the park's dance hall. Finally, Zophar saw the ghost—it stood 20 feet tall, then shrank into the form of Batty Malone. Zophar, of course, said he recognized Batty based on descriptions shared by people who knew him. Zophar raced into the park house and passed out. A week later, Zophar saw the ghost again, at the park’s open air theater, playing on the stage. This time the ghost ran away, disappearing under the lake’s water. Zophar and the ghost had several other encounters, leaving Zophar thoroughly terrorized.

Although the Herald mentioned that people in the Bucks Hill neighborhood discussed hunting down the ghost, I have yet to find any information about their supposed ghostbusting effort. What I have found is that Zophar appears to have died on June 21 1906, before the ghost story ran in the Bridgeport Herald. If Zophar really did claim to have been haunted shortly before he died, the story becomes extremely creepy! I need to do some legwork to confirm this sequence of events; there are several discrepancies that need clarifying. I’ll update this post once I get the details. For now, however, beware the ghost of Belleview Lake!

|

| Postcard view of the road and pond at main entrance to Lakewood Park, circa 1907. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

|

| Postcard view of Lakewood Park, circa 1907. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

Laura Pearsall’s personal life made the news once more before the end of her life. In October 1909, she married “Doctor” W. E. Ellsworth Jewell. By February of 1910, Laura was claiming that Jewell tricked her into marriage through hypnotism; she later asserted in the press that he “seemed possessed of the power of the devil which impelled me on and on.” Jewell tried to persuade Laura to give him one of her diamond rings, to convert to a tie-pin, and to let him subdivide Lakewood Park for housing. Laura was undecided about whether or not to divorce her hypnotic second husband, perhaps because her daughter had gone through a divorce in 1908.

Laura died in 1913. Laura’s granddaughter, Laura Linola Hylan, born 1891 in Waterbury, was her sole heir. Laura Linola led an even more flamboyant life than her grandmother, marrying four times and spending her days on the golf course. Nicknamed “Dolly,” she was romantically linked in the papers with Clark Gable in 1945 and ’46. When she married a Bulgarian perfume-maker in 1946, the papers declared “Clark Gable didn’t get the girl!” Dolly and Clark Gable remained close friends, reputedly rekindling their romance when her fourth husband died. When Dolly died in 1965, she was remembered as “an incomparable femme fatale” and “the ultimate female,” qualities she no doubt inherited from her grandmother, Laura Pearsall.

|

| Laura Pearsall's granddaughter and heir, Dolly O'Brien, with Clark Gable. From Fanpix.net |

Lakewood Park continued after the Pearsalls were gone, changing hands several times.

|

| Map showing Lakewood Park in green, 1932. A. J. Patton Map, Town Clerk's Office. |

Starting about 1921, the park was run by Dr. S.A. DeWaltoff and Robert J. Eustace. More than 61,000 people visited the park each year, dancing in the Roseland dance hall pavilion and bathing in the lake. The beach was expanded in 1922, with room for hundreds, possibly thousands, of people. A diving pier with multiple platforms was used for diving stunt performances. Schools used the beach for state swim meets during the 1920s, and various organizations held picnics in the wooded park. In 1928, the city seized the park for non-payment of taxes, and it has been a municipal park ever since--although with many significant changes over the years.

|

| Lakewood Boardwalk, looking toward the park, November 1937. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

|

| Lakewood Boardwalk, looking toward Larson's Restaurant (now Sav-A-Lot) on North Main Street, November 1937. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

|

| Miniature Golf trophy winners, 1920s. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

|

| Lakewood Park Roller Coaster, 1930s. Collection of Mattatuck Museum. |

|

| Lakewood Park Dance Pavilion, 1930s. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

|

| Lakewood Park beach and water attractions, 1930s. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

|

| Lakewood Park, 1930s. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

|

| Seating area at Lakewood Park, 1930s or '40s. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

|

| Lakewood Park, 1930s. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

|

| Lakewood Park, 1930s. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

|

| Lakewood Park advertisement, date unknown. Collection of City of Waterbury, Silas Bronson Library Digital Photos. |

The roller coast was sold in 1936 and is now the Yankee Cannonball ride at Canobie Lake Park in New Hampshire. The dance hall pavilion was demolished in 1952. Other features were gradually phased out as they deteriorated: a pavilion is all that remains of the merry-go-round. The park was expanded in 1952 when the city took ownership of the lake and 10 acres of shore, and again in 1958 with the Chase Company’s gift of over 100 acres of land surrounding the reservoir. Today, the park retains a small beach for swimming, facilities for picnics and large outdoor gatherings shaded by beautiful old trees, a playground, basketball court, and handball court.

5 comments:

Wow! What an amazing story!

Amazing story, Nice to piece of history to learn...TY

Amazing story and a nice piece of history to learn, too bad it cannot be made back into what some of it was back then...

It was an amazing park. Many well known dance bands were featured in the beautiful Grandstand. There were many stands of refreshment etc. ad well patronized. As a teenager it was only a few minutes walk from my home on North Main Street. At first we knew it as Luna Park one of its various names. But it soon was renamed Lakewood Park. I remember the Roller Coaster. It was great.

Thank you for giving us the history of Lakewood. It is a very interesting article.

Post a Comment